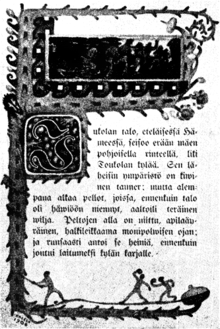

Seitsemän veljestä

The first words of the novel in Finnish | |

| Author | Aleksis Kivi |

|---|---|

| Translator | Alex Matson, Richard Impola, Douglas Robinson |

| Language | Finnish |

| Genre | Novel |

| Publisher | Finnish Literature Society |

Publication date | February 2, 1870[1] |

| Publication place | Finland |

Published in English | 1929 |

| Pages | 333 pp (four volumes) |

Seitsemän veljestä (Finnish pronunciation: [ˈsei̯tsemæn ˈʋeljestæ]; literally translated The Seven Brothers, or The Brothers Seven[2] in Douglas Robinson's 2017 translation) is the first and only novel by Aleksis Kivi, the national author of Finland.[3] It is widely regarded as the first significant novel written in Finnish and by a Finnish-speaking author, and is considered a real pioneer of Finnish realistic folklore. Some people still regard it as the greatest Finnish novel ever written,[4] and in time it has even gained the status of a "national novel of Finland".[3][5] The deep significance of the work for Finnish culture has even been quoted internationally, and in a BBC article by Lizzie Enfield, for example, which describes Kivi's Seitsemän veljestä as "the book that shaped a Nordic identity."[6]

Kivi began writing the work in the early 1860s and wrote it at least three times, but no manuscript has survived.[7] The work was largely created while Kivi lived in Siuntio's Fanjurkars with Charlotta Lönnqvist.[8] It was first published in 1870 in four volumes, but the publication of a one-volume novel did not happen until 1873, a year after the author's death.[7]

Reception history

[edit]Published in 1870, Seitsemän veljestä ended an era dominated by Swedish-speaking authors, most notable of whom was J. L. Runeberg, and created a solid basis for new Finnish authors like Minna Canth and Juhani Aho, who were, following Aleksis Kivi, the first authors to depict ordinary Finns in a realistic way.

The novel was particularly reviled by the literary circles of Kivi's time, who disliked the unflattering image of Finns it presented. The title characters were seen as crude caricatures of the nationalistic ideals of the time. Foremost in this hostile backlash was the influential critic August Ahlqvist, who called the book a "ridiculous work and a blot on the name of Finnish literature"[9] and wrote in a review published in Finlands Allmänna Tidning that "the brothers' characters were nothing like calm, serious and laborious folk who toiled the Finnish lands."[10][11] Another critic worth mentioning was the Fennoman politician Agathon Meurman, who, among other things, said the book was "a hellish lie about Finnish peasants" and stated that "Mr. Kivi regards the printing press as his poetic rectum."[5]

Literary scholar Markku Eskelinen considers Seitsemän veljestä to be very exceptional compared to his time of birth and the state of Finnish prose literature at that time. According to Eskelinen, the work is more tense and aesthetically complex than the realistic novels of the significant generation of writers who followed Kivi. Eskelinen also highlights Kivi's linguistic play with genres: although the work uses a lot of biblical and otherwise religious language for understandable reasons due to the dominance of religious literature at the time, its attitude to religious authority is not submissive, unlike other prose literature of the time. In Eskelinen's opinion, Finnish-language prose works comparable to the richness and multilevelness of Kivi's work began to appear only in the next century.[12]

The novel is referred to in the coat of arms of the Nurmijärvi municipality, the birthplace of Kivi. The explanation of the coat of arms is “in the blue field, the heads of seven young golden-haired young men set 2+3+2.” The coat of arms was designed by Olof Eriksson in accordance with the idea proposed by B. Harald Hellström, and was approved by the Nurmijärvi Municipal Council at its meeting on December 18, 1953. The coat of arms was approved for use by the Ministry of the Interior on April 14, 1954.[13][14]

Characters

[edit]Jukola brothers

[edit]- Juhani – at 25 years old the oldest brother. The leader of the group and also the most stubborn.

- Tuomas – scrupulous, strong as a bull, although Juhani claims to be the strongest brother.

- Aapo – twin-brother of Tuomas. Logical and peaceful.

- Simeoni – alcoholic and the most religious brother.

- Lauri – the most solemn brother, friend of nature and a loner.

- Timo – twin-brother of Lauri; simple and earnest.

- Eero – at 18 years old he is the youngest brother. Intelligent, clever, quarrelsome when confronted by Juhani.

Other

[edit]- Venla, a neighbor girl wooed by five of the seven brothers

Plot summary

[edit]At first, the brothers are not a particularly peaceful lot and end up quarreling with the local constable, juryman, vicar, churchwarden, and teachers—not to mention their neighbours in the village of Toukola. No wonder young girls' mothers do not regard them as good suitors. When the brothers are required to learn to read before they can accept church confirmation and therefore official adulthood—and the right to marry—they decide to run away.

Eventually they end up moving to distant Impivaara in the middle of relative wilderness, but their first efforts are shoddy—one Christmas Eve they end up burning down their sauna. The next spring they try again, but are forced to kill a nearby lord's herd of bulls and pay them back with wheat. Ten years of hard work clearing the forest for fields, hard drinking—and Simeoni's apocalyptic visions from delirium tremens—eventually lead them to mend their ways. They learn to read on their own and eventually return to Jukola.

In the end, most of them become pillars of the community and family men. Still, the tone of the tale is not particularly moralistic. Symbolically, the brothers represent the Finnish-speaking people and culture in the midst of external forces that force them to change.[15]

Translations

[edit]Seitsemän veljestä has been translated three times into English and 56 more times into 33 other languages.[16] Many significant Finnish artists have been responsible for illustrating the book, including Akseli Gallén-Kallela (1908), Marcus Collin (1948), Matti Visanti (1950), and Erkki Tanttu (1961).[17]

The first English edition was translated by Alexander Matson and published in 1929 by Coward-McCann.[18][19] Revised editions of Matson's translation were published in 1952 and 1973 by Tammi Publishers, with Irma Rantavaara conducting the third edition's revisions.[20]

A translation by Richard Impola was published in 1991 by the Finnish American Translators Association.[21] Douglas Robinson translated the book in 2017 under the title The Brothers Seven for Zeta Books in Bucharest.[22]

Adaptations

[edit]The Finnish National Theatre produced the first stage version of the novel in 1898 and Armas Launis composed the first Finnish comic opera based on the novel in 1913. The first film adaptation was made by Wilho Ilmari in 1939.[23]

In 1989, a television series called Seitsemän veljestä directed by Jouko Turkka caused wide controversy because of its portrayal of the brothers.[24]

The novel was adapted into a children's picture book in 2002 with all the characters changed into dogs or birds, which was titled The Seven Dog Brothers: Being a Doggerel Version of The Seven Brothers, Aleksis Kivi's Classic Novel from 1870.[25] The book was credited to Mauri Kunnas, a Finnish children's author, and Tarja Kunnas. Mr. Clutterbuck from Goodnight, Mr. Clutterbuck, also by Mauri Kunnas, makes an appearance in the story.[26]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Seitsemän veljestä 150 juhlavuosi – Nurmijärvi (in Finnish)

- ^ Aleksis Kivi: The Brothers Seven ('Seitsemän veljestä'), translated by Douglas Robinson (2017, Zeta Books)

- ^ a b Aleksis Kivi - Kansalliskirjailija (in Finnish)

- ^ See e.g. Aarne Kinnunen, Tuli, aurinko ja seitsemän veljestä: Tutkimus Aleksis Kiven romaanista (“Wind, Sun, and Seven Brothers: A Study of AK’s Novel”), p. 8. Porvoo and Helsinki: WSOY, 1973.

- ^ a b "Aleksis Kiven valtava klassikko sai ilmestyessään poikkeuksellisen teilauksen: "Poeettinen peräsuoli"". Ilta-Sanomat (in Finnish). 6 October 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ Enfield, Lizzie (September 8, 2021). "Seven Brothers: The book that shaped a Nordic identity". BBC. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ^ a b "Teokset". Aleksis Kivi - kansalliskirjailija. Archived from the original on April 18, 2016. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ Fanjunkarsin historia (in Finnish)

- ^ Liukkonen, Petri. "Aleksis Kivi". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 28 August 2005.

- ^ Korhonen, Anna. "Seitsemän veljestä". YLE (in Finnish). Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "Finsk litteratur VII". Finlands Allmänna Tidning (in Swedish). No. 116. May 21, 1870. pp. 2–3.

- ^ Markku Eskelinen (2016). Raukoilla rajoilla. Suomenkielisen proosakirjallisuuden historiaa (in Finnish). Siltala. pp. 70–72.

- ^ Suomen kunnallisvaakunat (in Finnish). Suomen Kunnallisliitto. 1982. p. 151. ISBN 951-773-085-3.

- ^ "Sisäasiainministeriön vahvistamat kaupunkien, kauppaloiden ja kuntien vaakunat 1949-1995 I:11 Nurmijärvi". Kansallisarkiston digitaaliarkisto (in Finnish). Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ "Aleksis Kivi: Seitsemän veljestä". Jyväskylän yliopisto. 23 February 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ Aleksis Kivi, the national author – web portal. See also Douglas Robinson, Aleksis Kivi and/as World Literature (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2017).

- ^ Otavan iso tietosanakirja, osa 4. Helsinki: Otava, 1962. (in Finnish)

- ^ "Alex (Alexander) Matson (1888-1972)". authorscalendar.info. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ Haq, Husna. "48 Hours: Helsinki". National Geographic Traveler. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ Aleksis Kivi, Seven Brothers. 1st edition, New York: Coward-McCann, 1929. 2nd edition, Helsinki: Tammi, 1952. 3rd edition, edited by Irma Rantavaara, Helsinki: Tammi, 1973. Note that Matson wrote his first name with the period ("Alex.") to indicate that it was a short form.

- ^ Aleksis Kivi, Seven Brothers. New Paltz, NY: Finnish-American Translators Association, 1991.

- ^ Aleksis Kivi, The Brothers Seven. Bucharest: Zeta Books, 2017

- ^ Seitsemän veljeksen tulkintoja ("Interpretations of the Seven Brothers")

- ^ Lindfors, Jukka (December 14, 2007). "Jouko Turkan Seitsemän veljestä". Elävä arkisto (in Finnish). YLE. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ Link text,

- ^ Kunnas, Mauri (21 May 2019). Goodnight, Mr. Clutterbuck. Steerforth Press. ISBN 9780914671763 – via Google Books.

External links

[edit]- The Aleksis Kivi Brothers Seven Translation Assessment Project, publicly accessible, provided by Hong Kong Baptist University Library

- 1890 Finnish text, at Project Runeberg.

- http://www.seitsemanveljesta.net/