Belgrade

Belgrade

Београд Beograd | |

|---|---|

| City of Belgrade Град Београд Grad Beograd | |

| Anthem: Химна Београду Himna Beogradu "Anthem to Belgrade" | |

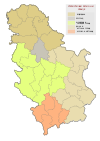

Belgrade in Serbia | |

| Coordinates: 44°49′04″N 20°27′25″E / 44.81778°N 20.45694°E | |

| Country | |

| City | Belgrade |

| Municipalities | 17 |

| Establishment | Prior to 279 B.C. (Singidunum)[2] |

| Government | |

| • Body | City Assembly of Belgrade |

| • Mayor | Aleksandar Šapić |

| • Ruling parties | SNS–SPS |

| Area | |

| 389.12 km2 (150.24 sq mi) | |

| • Urban | 1,035 km2 (400 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 3,234.96 km2 (1,249.03 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 117 m (384 ft) |

| Population (2022) | |

| 1,197,714[1] | |

| • Density | 3,078/km2 (7,970/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,383,875[5] |

| • Urban density | 1,337/km2 (3,460/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,685,563[4] |

| • Metro density | 520/km2 (1,300/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Belgradian (en) Beograđanin (Београђанин) (m.) Beograđanka (Београђанка) (f.) (sr) |

| GDP | |

| • Metro | $34.141 billion (2022) |

| • Per capita (nominal) | $20,260 (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 11000 |

| Area code | +381(0)11 |

| ISO 3166 code | RS-00 |

| Vehicle registration | BG |

| International Airport | Belgrade Nikola Tesla Airport (BEG) |

| Website | beograd.rs |

Belgrade (/bɛlˈɡreɪd/ bel-GRAYD, /ˈbɛlɡreɪd/ BEL-grayd;[a] Serbian: Београд / Beograd, lit. 'White City', pronounced [beǒɡrad] ⓘ) is the capital and largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and at the crossroads of the Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula.[10] The population of the Belgrade metropolitan area is 1,685,563 according to the 2022 census.[4] It is one of the major cities of Southeast Europe and the third most populous city on the Danube river.

Belgrade is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Europe and the world. One of the most important prehistoric cultures of Europe, the Vinča culture, evolved within the Belgrade area in the 6th millennium BC. In antiquity, Thraco-Dacians inhabited the region and, after 279 BC, Celts settled the city, naming it Singidūn.[11] It was conquered by the Romans under the reign of Augustus and awarded Roman city rights in the mid-2nd century.[12] It was settled by the Slavs in the 520s, and changed hands several times between the Byzantine Empire, the Frankish Empire, the Bulgarian Empire, and the Kingdom of Hungary before it became the seat of the Serbian king Stefan Dragutin in 1284. Belgrade served as capital of the Serbian Despotate during the reign of Stefan Lazarević, and then his successor Đurađ Branković returned it to the Hungarian king in 1427. Noon bells in support of the Hungarian army against the Ottoman Empire during the siege in 1456 have remained a widespread church tradition to this day. In 1521, Belgrade was conquered by the Ottomans and became the seat of the Sanjak of Smederevo.[13] It frequently passed from Ottoman to Habsburg rule, which saw the destruction of most of the city during the Ottoman–Habsburg wars.

Following the Serbian Revolution, Belgrade was once again named the capital of Serbia in 1841. Northern Belgrade remained the southernmost Habsburg post until 1918, when it was attached to the city, due to former Austro-Hungarian territories becoming part of the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes after World War I. Belgrade was the capital of Yugoslavia from its creation to its dissolution.[note 1] In a fatally strategic position, the city has been battled over in 115 wars and razed 44 times, being bombed five times and besieged many times.[14]

Being Serbia's primate city, Belgrade has special administrative status within Serbia.[15] It is the seat of the central government, administrative bodies, and government ministries, as well as home to almost all of the largest Serbian companies, media, and scientific institutions. Belgrade is classified as a Beta-Global City.[16] The city is home to the University Clinical Centre of Serbia, a hospital complex with one of the largest capacities in the world; the Church of Saint Sava, one of the largest Orthodox church buildings; and the Belgrade Arena, one of the largest capacity indoor arenas in Europe.

Belgrade hosted major international events such as the Danube River Conference of 1948, the first Non-Aligned Movement Summit (1961), the first major gathering of the OSCE (1977–1978), the Eurovision Song Contest (2008), as well as sports events such as the first FINA World Aquatics Championships (1973), UEFA Euro (1976), Summer Universiade (2009) and EuroBasket three times (1961, 1975, 2005). On 21 June 2023, Belgrade was confirmed host of the BIE- Specialized Exhibition Expo 2027.[17]

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]

Chipped stone tools found in Zemun show that the area around Belgrade was inhabited by nomadic foragers in the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic eras. Some of these tools are of Mousterian industry—belonging to Neanderthals rather than modern humans. Aurignacian and Gravettian tools have also been discovered near the area, indicating some settlement between 50,000 and 20,000 years ago.[18] The first farming people to settle in the region are associated with the Neolithic Starčevo culture, which flourished between 6200 and 5200 BC.[19] There are several Starčevo sites in and around Belgrade, including the eponymous site of Starčevo. The Starčevo culture was succeeded by the Vinča culture (5500–4500 BC), a more sophisticated farming culture that grew out of the earlier Starčevo settlements and also named for a site in the Belgrade region (Vinča-Belo Brdo). The Vinča culture is known for its very large settlements, one of the earliest settlements by continuous habitation and some of the largest in prehistoric Europe.[20] Also associated with the Vinča culture are anthropomorphic figurines such as the Lady of Vinča, the earliest known copper metallurgy in Europe,[21] and a proto-writing form developed prior to the Sumerians and Minoans known as the Old European script, which dates back to around 5300 BC.[22] Within the city proper, on Cetinjska Street, a skull of a Paleolithic human dated to before 5000 BC was discovered in 1890.[23]

Antiquity

[edit]

Evidence of early knowledge about Belgrade's geographical location comes from a variety of ancient myths and legends. The ridge overlooking the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers, for example, has been identified as one of the places in the story of Jason and the Argonauts.[24][25] In the time of antiquity, too, the area was populated by Paleo-Balkan tribes, including the Thracians and the Dacians, who ruled much of Belgrade's surroundings.[26] Specifically, Belgrade was at one point inhabited by the Thraco-Dacian tribe Singi;[11] following Celtic invasion in 279 BC, the Scordisci wrested the city from their hands, naming it Singidūn (d|ūn, fortress).[11] In 34–33 BC, the Roman army reached Belgrade. It became the romanised Singidunum in the 1st century AD and, by the mid-2nd century, the city was proclaimed a municipium by the Roman authorities, evolving into a full-fledged colonia (the highest city class) by the end of the century.[12] While the first Christian Emperor of Rome—Constantine I, also known as Constantine the Great[27]—was born in the territory of Naissus to the city's south, Roman Christianity's champion, Flavius Iovianus (Jovian/Jovan), was born in Singidunum.[28] Jovian reestablished Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire, ending the brief revival of traditional Roman religions under his predecessor Julian the Apostate. In 395 AD, the site passed to the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire.[29] Across the Sava from Singidunum was the Celtic city of Taurunum (Zemun); the two were connected with a bridge throughout Roman and Byzantine times.[30]

Middle Ages

[edit]

In 442, the area was ravaged by Attila the Hun.[31] In 471, it was taken by Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths, who continued into Italy.[32] As the Ostrogoths left, another Germanic tribe, the Gepids, invaded the city. In 539, it was retaken by the Byzantines.[33] In 577, some 100,000 Slavs poured into Thrace and Illyricum, pillaging cities and more permanently settling the region. [34]

The Avars, under Bayan I, conquered the whole region and its new Slavic population by 582.[35] Following Byzantine reconquest, the Byzantine chronicle De Administrando Imperio mentions the White Serbs, who had stopped in Belgrade on their way back home, asking the strategos for lands; they received provinces in the west, towards the Adriatic, which they would rule as subjects to Heraclius (610–641).[36] In 829, Khan Omurtag was able to add Singidunum and its environs to the First Bulgarian Empire.[37][38] The first record of the name Belograd appeared on April, 16th, 878, in a Papal missive[39] to Bulgarian ruler Boris I. This name would appear in several variants: Alba Bulgarica in Latin, Griechisch Weissenburg in High German, Nándorfehérvár in Hungarian, and Castelbianco in Venetian, among other names, all variations of 'white fortress' or 'Bulgar white fortress'. For about four centuries, the city would become a battleground between the Byzantine Empire, the medieval Kingdom of Hungary, and the Bulgarian Empire.[40] Basil II (976–1025) installed a garrison in Belgrade.[41] The city hosted the armies of the First and the Second Crusade,[42] but, while passing through during the Third Crusade, Frederick Barbarossa and his 190,000 crusaders saw Belgrade in ruins.[43]

King Stefan Dragutin (r. 1276–1282) received Belgrade from his father-in-law, Stephen V of Hungary, in 1284, and it served as the capital of the Kingdom of Syrmia, a vassal state to the Kingdom of Hungary. Dragutin (Hungarian: Dragutin István) is regarded as the first Serbian king to rule over Belgrade.[44]

Following the battles of Maritsa (1371) and Kosovo field (1389), Moravian Serbia, to Belgrade's south, began to fall to the Ottoman Empire.[45][46]

The northern regions of what is now Serbia persisted as the Serbian Despotate, with Belgrade as its capital. The city flourished under Stefan Lazarević, the son of Serbian prince Lazar Hrebeljanović. Lazarević built a castle with a citadel and towers, of which only the Despot's tower and the west wall remain. He also refortified the city's ancient walls, allowing the Despotate to resist Ottoman conquest for almost 70 years. During this time, Belgrade was a haven for many Balkan peoples fleeing Ottoman rule, and is thought to have had a population ranging between 40,000 and 50,000 people.[44]

In 1427, Stefan's successor Đurađ Branković, returning Belgrade to the Hungarian king, made Smederevo his new capital. Even though the Ottomans had captured most of the Serbian Despotate, Belgrade, known as Nándorfehérvár in Hungarian, was unsuccessfully besieged in 1440[42] and 1456.[47] As the city presented an obstacle to the Ottoman advance into Hungary and further, over 100,000 Ottoman soldiers[48] besieged it in 1456, in which the Christian army led by the Hungarian General John Hunyadi successfully defended it.[49] The noon bell ordered by Pope Callixtus III commemorates the victory throughout the Christian world to this day, which is now a cultural symbol of Hungary.[42][50]

Ottoman rule and Austrian invasions

[edit]

Seven decades after the initial siege, on 28 August 1521, the fort was finally captured by Suleiman the Magnificent with 250,000 Turkish soldiers and over 100 ships. Subsequently, most of the city was razed to the ground and its entire Orthodox Christian population was deported to Istanbul[42][51] to an area that has since become known as the Belgrade forest.[52]

Belgrade was made the seat of the Pashalik of Belgrade (also known as the Sanjak of Smederevo), and quickly became the second largest Ottoman town in Europe at over 100,000 people, surpassed only by Constantinople.[48] Ottoman rule introduced Ottoman architecture, including numerous mosques, and the city was resurrected—now by Oriental influences.[53]

In 1594, a major Serb rebellion was crushed by the Ottomans. In retribution, Grand Vizier Sinan Pasha ordered the relics of Saint Sava to be publicly torched on the Vračar plateau; in the 20th century, the church of Saint Sava was built to commemorate this event.[54]

Occupied by the Habsburgs three times (1688–1690, 1717–1739, 1789–1791), headed by the Holy Roman Princes Maximilian of Bavaria and Eugene of Savoy,[55] and field marshal Baron Ernst Gideon von Laudon, respectively, Belgrade was quickly recaptured by the Ottomans and substantially razed each time.[53] During this period, the city was affected by the two Great Serbian Migrations, in which hundreds of thousands of Serbs, led by two Serbian Patriarchs, retreated together with the Austrian soldiers into the Habsburg Empire, settling in today's Vojvodina and Slavonia.[56]

Principality and Kingdom of Serbia

[edit]

At the beginning of the 19th century, Belgrade was predominantly inhabited by a Muslim population. Traces of Ottoman rule and architecture—such as mosques and bazaars, were to remain a prominent part of Belgrade's townscape into the 19th century; several decades, even, after Serbia was granted autonomy from the Ottoman Empire.[57]

During the First Serbian Uprising, Serbian revolutionaries held the city from 8 January 1807 until 1813, when it was retaken by the Ottomans.[58] In 1807, Turks in Belgrade were massacred and forcefully converted to Christianity. The massacre was encouraged by Russia in order to cement divisions between the Serb rebels and the Porte. Around 6,000 Muslims and Jews were forcibly converted to Christianity. Most mosques were converted into churches. Muslims, Jews, Aromanians and Greeks were subjected to forced labour, and Muslim women were widely made available to young Serb men, and some were taken into slavery. Milenko Stojković bought many of them, and established his harem for which he gained fame. In this circumstances Belgrade demographically transformed from Ottoman to Serb.[59] After the Second Serbian Uprising in 1815, Serbia achieved some sort of sovereignty, which was formally recognised by the Porte in 1830.[60]

The development of Belgrade architecture after 1815 can be divided into four periods. In the first phase, which lasted from 1815 to 1835, the dominant architectural style was still of a Balkan character, with substantial Ottoman influence. At the same time, an interest in joining the European mainstream allowed Central and Western European architecture to flourish. Between 1835 and 1850, the amount of neoclassicist and baroque buildings south of the Austrian border rose considerably, exemplified by St Michael's Cathedral (Serbian: Saborna crkva), completed in 1840. Between 1850 and 1875, new architecture was characterised by a turn towards the newly popular Romanticism, along with older European architectural styles. Typical of Central European cities in the last quarter of the 19th century, the fourth phase was characterised by an eclecticist style based on the Renaissance and Baroque periods.[61]

In 1841, Prince Mihailo Obrenović moved the capital of the Principality of Serbia from Kragujevac to Belgrade.[62][63] During his first reign (1815–1839), Prince Miloš Obrenović pursued expansion of the city's population through the addition of new settlements, aiming and succeeding to make Belgrade the centre of the Principality's administrative, military and cultural institutions. His project of creating a new market space (the Abadžijska čaršija), however, was less successful; trade continued to be conducted in the centuries-old Donja čaršija and Gornja čaršija. Still, new construction projects were typical for the Christian quarters as the older Muslim quarters declined; from Serbia's autonomy until 1863, the number of Belgrade quarters even decreased, mainly as a consequence of the gradual disappearance of the city's Muslim population. An Ottoman city map from 1863 counts only 9 Muslim quarters (mahalas). The names of only five such neighbourhoods are known today: Ali-pašina, Reis-efendijina, Jahja-pašina, Bajram-begova, and Laz Hadži-Mahmudova.[64] Following the Čukur Fountain incident, Belgrade was bombed by the Ottomans.[65]

On 18 April 1867, the Ottoman government ordered the Ottoman garrison, which had been since 1826 the last representation of Ottoman suzerainty in Serbia, withdrawn from Kalemegdan. The forlorn Porte's only stipulation was that the Ottoman flag continue to fly over the fortress alongside the Serbian one. Serbia's de facto independence dates from this event.[66] In the following years, urban planner Emilijan Josimović had a significant influence on Belgrade. He conceptualised a regulation plan for the city in 1867, in which he proposed the replacement of the town's crooked streets with a grid plan. Of great importance also was the construction of independent Serbian political and cultural institutions, as well as the city's now-plentiful parks. Pointing to Josimović's work, Serbian scholars have noted an important break with Ottoman traditions. However, Istanbul—the capital city of the state to which Belgrade and Serbia de jure still belonged—underwent similar changes.[67]

In May 1868, knez Mihailo was assassinated with his cousin Anka Konstantinović while riding in a carriage in his country residence.[68]

With the Principality's full independence in 1878 and its transformation into the Kingdom of Serbia in 1882, Belgrade once again became a key city in the Balkans, and developed rapidly.[58][69] Nevertheless, conditions in Serbia remained those of an overwhelmingly agrarian country, even with the opening of a railway to Niš, Serbia's second city. In 1900, the capital had only 70,000 inhabitants[70] (at the time Serbia numbered 2.5 million). Still, by 1905, the population had grown to more than 80,000 and, by the outbreak of World War I in 1914, it had surpassed the 100,000 citizens, disregarding Zemun, which still belonged to Austria-Hungary.[71]

The first-ever projection of motion pictures in the Balkans and Central Europe was held in Belgrade in June 1896 by André Carr, a representative of the Lumière brothers. He shot the first motion pictures of Belgrade in the next year; however, they have not been preserved.[72] The first permanent cinema was opened in 1909 in Belgrade.[73]

World War I: Austro–German invasion

[edit]

The First World War began on 28 July 1914 when Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. Most of the subsequent Balkan offensives occurred near Belgrade. Austro-Hungarian monitors shelled Belgrade on 29 July 1914, and it was taken by the Austro-Hungarian Army under General Oskar Potiorek on 1 December. On 16 December, it was re-taken by Serbian troops under Marshal Radomir Putnik. After a prolonged battle which destroyed much of the city, starting on 6 October 1915, Belgrade fell to German and Austro-Hungarian troops commanded by Field Marshal August von Mackensen on 9 October of the same year. The city was liberated by Serbian and French troops on 1 November 1918, under the command of Marshal Louis Franchet d'Espèrey of France and Crown Prince Alexander of Serbia. Belgrade, devastated as a front-line city, lost the title of largest city in the Kingdom to Subotica for some time.[74]

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

[edit]After the war, Belgrade became the capital of the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929. The Kingdom was split into banovinas and Belgrade, together with Zemun and Pančevo, formed a separate administrative unit.[75] During this period, the city experienced fast growth and significant modernisation. Belgrade's population grew to 239,000 by 1931 (with the inclusion of Zemun), and to 320,000 by 1940. The population growth rate between 1921 and 1948 averaged 4.08% a year.[76]

In 1927, Belgrade's first airport opened, and in 1929, its first radio station began broadcasting. The Pančevo Bridge, which crosses the Danube, was opened in 1935,[77] while King Alexander Bridge over the Sava was opened in 1934. On 3 September 1939 the first Belgrade Grand Prix, the last Grand Prix motor racing race before the outbreak of World War II, was held around the Belgrade Fortress and was followed by 80,000 spectators.[78] The winner was Tazio Nuvolari.[79]

World War II: German invasion

[edit]

On 25 March 1941, the government of regent Crown Prince Paul signed the Tripartite Pact, joining the Axis powers in an effort to stay out of the Second World War and keep Yugoslavia neutral during the conflict. This was immediately followed by mass protests in Belgrade and a military coup d'état led by Air Force commander General Dušan Simović, who proclaimed King Peter II to be of age to rule the realm. As a result, the city was heavily bombed by the Luftwaffe on 6 April 1941, killing up to 2,274 people.[80][81][82] Yugoslavia was then invaded by German, Italian, Hungarian, and Bulgarian forces. Belgrade was captured by subterfuge, with six German soldiers led by their officer Fritz Klingenberg feigning threatening size, forcing the city to capitulate.

[83] Belgrade was more directly occupied by the German Army in the same month and became the seat of the puppet Nedić regime, headed by its namesake general.[84] Some of today's parts of Belgrade were incorporated in the Independent State of Croatia in occupied Yugoslavia, another puppet state, where Ustashe regime carried out the Genocide of Serbs.[85]

During the summer and autumn of 1941, in reprisal for guerrilla attacks, the Germans carried out several massacres of Belgrade citizens; in particular, members of the Jewish community were subject to mass shootings at the order of General Franz Böhme, the German Military Governor of Serbia. Böhme rigorously enforced the rule that for every German killed, 100 Serbs or Jews would be shot.[86] Belgrade became the first city in Europe to be declared by the Nazi occupation forces to be judenfrei.[87] The resistance movement in Belgrade was led by Major Žarko Todorović from 1941 until his arrest in 1943.[88]

Just like Rotterdam, which was devastated twice by both German and Allied bombing, Belgrade was bombed once more during World War II, this time by the Allies on 16 April 1944, killing at least 1,100 people. This bombing fell on the Orthodox Christian Easter.[89] Most of the city remained under German occupation until 20 October 1944, when it was liberated by the Red Army and the Communist Yugoslav Partisans.

On 29 November 1945, Marshal Josip Broz Tito proclaimed the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia in Belgrade (later renamed to Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia on 7 April 1963).[90]

Socialist Yugoslavia

[edit]

When the war ended, the city was left with 11,500 demolished housing units.[91] During the post-war period, Belgrade grew rapidly as the capital of the renewed Yugoslavia, developing as a major industrial centre.[69]

In 1948, construction of New Belgrade started. In 1958, Belgrade's first television station began broadcasting. In 1961, Belgrade hosted the first and founding conference of the Non-Aligned Movement under Tito's chairmanship.[92] In 1962, Belgrade Nikola Tesla Airport was built. In 1968, major student protests led to several street clashes between students and the police.[93]

In 1972, Belgrade faced a smallpox outbreak, the last major outbreak of smallpox in Europe since World War II.[94] Between October 1977 and March 1978, the city hosted the first major gathering of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe with the aim of implementing the Helsinki Accords from, while in 1980 Belgrade hosted the UNESCO General Conference.[95] Josip Broz Tito died in May 1980 and his funeral in Belgrade was attended by high officials and state delegations from 128 of the 154 members of the United Nations from all over the world, based on which it became one of the largest funerals in history.[96]

Breakup of Yugoslavia

[edit]

On 9 March 1991, massive demonstrations led by Vuk Drašković were held in the city against Slobodan Milošević.[97] According to various media outlets, there were between 100,000 and 150,000 people on the streets.[98] Two people were killed, 203 were injured and 108 were arrested during the protests, and later that day tanks were deployed onto the streets to restore order.[99] Many anti-war protests were held in Belgrade, with the largest protests being dedicated to solidarity with the victims from the besieged Sarajevo.[100][101] Further anti-government protests were held in Belgrade from November 1996 to February 1997 against the same government after alleged electoral fraud in local elections.[102] These protests brought Zoran Đinđić to power, the first mayor of Belgrade since World War II who did not belong to the League of Communists of Yugoslavia or its later offshoot, the Socialist Party of Serbia.[103]

In 1999, during the Kosovo War, the NATO bombing campaign targeted a number a buildings in Belgrade. Among the sites bombed were some ministry buildings, the RTS building, hospitals, Hotel Jugoslavija, the Central Committee building, Avala Tower, and the Chinese embassy.[104] Between 500[105] and 2,000 civilians[106] were killed in Serbia and Montenegro as a result of the NATO bombings, of which 47 were killed in Belgrade.[107] After the Yugoslav Wars, Serbia became home to the highest number of refugees and internally displaced persons in Europe, with more than a third of these refugees having settled in Belgrade.[108][109][110][111]

After the 2000 presidential elections, Belgrade was the site of major public protests, with over half a million people taking part. These demonstrations resulted in the ousting of president Milošević as a part of the Otpor movement.[112][113]

Development

[edit]

In 2014, Belgrade Waterfront, an urban renewal project, was initiated by the Government of Serbia and its Emirati partner, Eagle Hills Properties. Around €3.5 billion was to be jointly invested by the Serbian government and their Emirati partners.[114][needs update] The project includes office and luxury apartment buildings, five-star hotels, a shopping mall and the envisioned 'Belgrade Tower'. The project is, however, quite controversial—there are a number of uncertainties regarding its funding, necessity, and its architecture's arguable lack of harmony with the rest of the city.[115]

In addition to Belgrade Waterfront, the city is under rapid development and reconstruction, especially in the area of Novi Beograd, where (as of 2020) apartment and office buildings were under construction to support the burgeoning Belgrade IT sector, now one of Serbia's largest economic players. In September 2020, there were around 2000 active construction sites in Belgrade.[116] The city budget for 2023 stood at 205,5 billion dinars (1.750 billion Euros).[117] The budget for the city of Belgrade has been estimated to be more than 2 billion Euros for 2024.

Geography

[edit]Topography

[edit]

Belgrade lies 116.75 m (383.0 ft) above sea level and is located at the confluence of the Danube and Sava rivers.[14] The historical core of Belgrade, Kalemegdan, lies on the right banks of both rivers. Since the 19th century, the city has been expanding to the south and east; after World War II, New Belgrade was built on the left bank of the Sava river, connecting Belgrade with Zemun. Smaller, chiefly residential communities across the Danube, like Krnjača, Kotež and Borča, also merged with the city, while Pančevo, a heavily industrialised satellite city, remains separate. The city has an urban area of 360 km2 (140 sq mi), while together with its metropolitan area it covers 3,223 km2 (1,244 sq mi).[11]

On the right bank of the Sava, central Belgrade has a hilly terrain, while the highest point of Belgrade proper is Torlak hill at 303 m (994 ft). The mountains of Avala (511 m (1,677 ft)) and Kosmaj (628 m (2,060 ft)) lie south of the city. Across the Sava and Danube, the land is mostly flat, consisting of alluvial plains and loessial plateaus.[118]

One of the characteristics of the city terrain is mass wasting. On the territory covered by the General Urban Plan there are 1,155 recorded mass wasting points, out of which 602 are active and 248 are labeled as 'high risk'. They cover almost 30% of the city territory and include several types of mass wasting. Downhill creeps are located on the slopes above the rivers, mostly on the clay or loam soils, inclined between 7 and 20%. The most critical ones are in Karaburma, Zvezdara, Višnjica, Vinča and Ritopek, in the Danube valley, and Umka, and especially its neighbourhood of Duboko, in the Sava valley. They have moving and dormant phases, and some of them have been recorded for centuries. Less active downhill creep areas include the entire Terazije slope above the Sava (Kalemegdan, Savamala), which can be seen by the inclination of the Pobednik monument and the tower of the Cathedral Church, and the Voždovac section, between Banjica and Autokomanda.

Landslides encompass smaller areas, develop on the steep cliffs, sometimes being inclined up to 90%. They are mostly located in the artificial loess hills of Zemun: Gardoš, Ćukovac and Kalvarija.

However, the majority of the land movement in Belgrade, some 90%, is triggered by the construction works and faulty water supply system (burst pipes, etc.). The neighbourhood of Mirijevo is considered to be the most successful project of fixing the problem. During the construction of the neighbourhood from the 1970s, the terrain was systematically improved and the movement of the land is today completely halted.[119][120]

Climate

[edit]Under the Köppen climate classification, Belgrade has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) bordering on a humid continental climate (Dfa) with four seasons and uniformly spread precipitation. Monthly averages range from 1.9 °C (35.4 °F) in January to 23.8 °C (74.8 °F) in July, with an annual mean of 13.2 °C (55.8 °F). There are, on average, 44.6 days a year when the maximum temperature is at or above 30 °C (86 °F),[121] and 95 days when the temperature is above 25 °C (77 °F), On the other hand, Belgrade experiences 52.1 days per year in which the minimum temperature falls below 0 °C (32 °F), with 13.8 days having a maximum temperature below freezing as well.[121] Belgrade receives about 698 mm (27 in) of precipitation a year, with late spring being wettest. The average annual number of sunny hours is 2,020.

Belgrade may experience thunderstorms at any time of the year, experiencing 31 days annually, but it's much more common in spring and summer months. Hail is rare and occurs exclusively in spring or summer.[121]

The highest officially recorded temperature in Belgrade was 43.6 °C (110.5 °F) on 24 July 2007,[122] while on the other end, the lowest temperature was −26.2 °C (−15 °F) on 10 January 1893.[123] The highest recorded value of daily precipitation was 109.8 millimetres (4.32 inches) on 15 May 2014.[121]

| Climate data for Belgrade (1991–2020, extremes 1920–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.7 (69.3) |

23.9 (75.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

32.4 (90.3) |

34.9 (94.8) |

38.7 (101.7) |

43.6 (110.5) |

41.8 (107.2) |

41.8 (107.2) |

34.7 (94.5) |

29.3 (84.7) |

22.7 (72.9) |

43.6 (110.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

7.8 (46.0) |

13.1 (55.6) |

18.9 (66.0) |

23.6 (74.5) |

27.1 (80.8) |

29.3 (84.7) |

29.7 (85.5) |

24.3 (75.7) |

18.7 (65.7) |

12.2 (54.0) |

6.1 (43.0) |

18.0 (64.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.9 (35.4) |

3.8 (38.8) |

8.3 (46.9) |

13.6 (56.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

21.9 (71.4) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.8 (74.8) |

18.5 (65.3) |

13.3 (55.9) |

8.1 (46.6) |

3.0 (37.4) |

13.2 (55.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −0.7 (30.7) |

0.6 (33.1) |

4.2 (39.6) |

8.8 (47.8) |

13.2 (55.8) |

16.7 (62.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

18.5 (65.3) |

14.1 (57.4) |

9.4 (48.9) |

5.1 (41.2) |

0.5 (32.9) |

9.1 (48.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −26.2 (−15.2) |

−25.5 (−13.9) |

−14.4 (6.1) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

4.6 (40.3) |

8.3 (46.9) |

6.7 (44.1) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−19.3 (−2.7) |

−26.2 (−15.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 47.9 (1.89) |

43.5 (1.71) |

48.7 (1.92) |

51.5 (2.03) |

72.3 (2.85) |

95.6 (3.76) |

66.5 (2.62) |

55.1 (2.17) |

58.6 (2.31) |

54.8 (2.16) |

49.6 (1.95) |

54.8 (2.16) |

698.9 (27.52) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 13.5 | 12.3 | 11.3 | 12.4 | 13.5 | 12.2 | 10.0 | 8.4 | 9.5 | 10.5 | 10.8 | 13.8 | 138.2 |

| Average snowy days | 9.7 | 7.3 | 4.2 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 3.0 | 7.8 | 32.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 77.9 | 71.4 | 62.7 | 59.9 | 61.9 | 62.5 | 59.8 | 59.5 | 65.8 | 71.4 | 75.1 | 79.5 | 67.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 70.7 | 96.2 | 146.7 | 186.7 | 224.7 | 253.9 | 278.8 | 262.6 | 192.6 | 155.0 | 92.1 | 60.3 | 2,020.3 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Source 1: Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia[124] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (UV),[125] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[126] | |||||||||||||

Administration

[edit]Belgrade is a separate territorial unit in Serbia, with its own autonomous city authority.[15] The Assembly of the City of Belgrade has 110 members, elected on four-year terms.[127] A 13-member City Council, elected by the Assembly and presided over by the mayor and his deputy, has the control and supervision of the city administration,[128] which manages day-to-day administrative affairs. It is divided into 14 Secretariats, each having a specific portfolio such as traffic or health care, and several professional services, agencies and institutes.[129]

The 2022 Belgrade City Assembly election was won by the Serbian Progressive Party, which formed a ruling coalition with the Socialist Party of Serbia. Between 2004 and 2013, the Democratic Party was in power.[130] Due to the importance of Belgrade in political and economic life of Serbia, the office of city's mayor is often described as the third most important office in the state, after the President of the Government and the President of the Republic.[131][132][133]

As the capital city, Belgrade is seat of all Serbian state authorities – executive, legislative, judiciary, and the headquarters of almost all national political parties as well as 75 diplomatic missions.[134] This includes the National Assembly, the Presidency, the Government of Serbia and all the ministries, Supreme Court of Cassation and the Constitutional Court.

Municipalities

[edit]

The city is divided into 17 municipalities.[135] Previously, they were classified into 10 urban (lying completely or partially within borders of the city proper) and 7 suburban municipalities, whose centres are smaller towns.[136] With the new 2010 City statute, they were all given equal status, with the proviso that suburban ones (except Surčin) have certain autonomous powers, chiefly related with construction, infrastructure and public utilities.[135]

Most of the municipalities are situated on the southern side of the Danube and Sava rivers, in the Šumadija region. Three municipalities (Zemun, Novi Beograd, and Surčin), are on the northern bank of the Sava in the Syrmia region and the municipality of Palilula, spanning the Danube, is in both the Šumadija and Banat regions.

| Municipality | Classification | Area (km2) | Population (census 2022) | Population density (per km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barajevo | suburban | 213.10 | 26,431 | 110 |

| Čukarica | urban | 156.99 | 175,793 | 1,120 |

| Grocka | suburban | 299.55 | 82,810 | 276 |

| Lazarevac | suburban | 383.51 | 55,146 | 144 |

| Mladenovac | suburban | 339 | 48,683 | 144 |

| Novi Beograd | urban | 40.71 | 209,763 | 5,153 |

| Obrenovac | suburban | 410.14 | 68,882 | 168 |

| Palilula | urban | 450.59 | 182,624 | 405 |

| Rakovica | urban | 30.11 | 104,456 | 3,469 |

| Savski Venac | urban | 14.06 | 36,699 | 2,610 |

| Sopot | suburban | 270.71 | 19,126 | 71 |

| Stari Grad | urban | 5.40 | 44,737 | 8,285 |

| Surčin | urban | 288.47 | 45,452 | 158 |

| Voždovac | urban | 148.52 | 174,864 | 1,177 |

| Vračar | urban | 2.87 | 55,406 | 19,305 |

| Zemun | urban | 149.74 | 177,908 | 1,188 |

| Zvezdara | urban | 31.49 | 172,625 | 5,482 |

| Total | 3,234.96 | 1,681,405 | 520 | |

| Source: Sector for statistics, Belgrade[3] | ||||

Demographics

[edit]

According to the 2022 census, the statistical city proper has a population of 1,197,714, the urban area (with adjacent urban settlements like Borča, Ovča, Surčin, etc.) has 1,383,875 inhabitants, while the population of the administrative area of the City of Belgrade (often equated with Belgrade's metropolitan area) stands at 1,681,405 people. However, Belgrade's metropolitan area has not been defined, either statistically or administratively, and it sprawls into the neighboring municipalities like Pančevo, Opovo, Pećinci or Stara Pazova.

Belgrade is home to many ethnicities from across the former Yugoslavia and the wider Balkans region. The main ethnic group comprising over 86% of the metropolitan population of Belgrade are Serbs (1,449,241). Some significant minorities include Roma (23,160), Yugoslavs (10,499), Gorani (5,249), Montenegrins (5,134), Russians (4,659), Croats (4,554), Macedonians (4,293), and ethnic Muslims (2,718).[137] Many people came to the city as economic migrants from smaller towns and the countryside, while tens of thousands arrived as refugees from Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo, as a result of the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s.[138] The most recent wave of immigration following the Russian invasion of Ukraine saw tens of thousands of Russians and Ukrainians register their residence in Serbia, majority of them in Belgrade.[139]

Between 10,000 and 20,000[140] Chinese people are estimated to live in Belgrade and, since their arrival in the mid-1990s, Block 70 in New Belgrade has been known colloquially as the Chinese quarter.[141][142] Many Middle Easterners, mainly from Syria, Iran, Jordan and Iraq, arrived in order to pursue their studies during the 1970s and 1980s, and have remained in the city.[143] Throughout the 19th and early 20th century, small communities of Aromanians, Czechs, Greeks, Germans, Hungarians, Jews, Turks, Armenians and Russian White émigrés also existed in Belgrade. There are two suburban settlements with significant minority population today: Ovča and the village of Boljevci, both with about one quarter of their population being Romanians and Slovaks, respectively. Immigration to Belgrade from other countries accelerates. In 2023, more than 30,000 foreign workers got working and residence permits only in Belgrade.[144]

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1426 | 50,000 | — |

| 1683 | 100,000 | +0.27% |

| 1800 | 25,000 | −1.18% |

| 1834 | 7,033 | −3.66% |

| 1859 | 18,860 | +4.02% |

| 1863 | 14,760 | −5.94% |

| 1866 | 24,768 | +18.83% |

| 1874 | 27,605 | +1.36% |

| 1884 | 35,483 | +2.54% |

| 1890 | 54,763 | +7.50% |

| 1895 | 59,790 | +1.77% |

| 1900 | 68,481 | +2.75% |

| 1905 | 77,235 | +2.44% |

| 1910 | 82,498 | +1.33% |

| 1921 | 111,739 | +2.80% |

| 1931 | 238,775 | +7.89% |

| 1948 | 397,911 | +3.05% |

| 1953 | 477,982 | +3.73% |

| 1961 | 657,362 | +4.06% |

| 1971 | 899,094 | +3.18% |

| 1981 | 1,087,915 | +1.92% |

| 1991 | 1,133,146 | +0.41% |

| 2002 | 1,119,642 | −0.11% |

| 2011 | 1,166,763 | +0.46% |

| 2022 | 1,197,714 | +0.24% |

| Source: 1426-1683 data;[145] 1800 data;[146] 1834-1931[147] | ||

| Settlements | Population [148] |

|---|---|

| Belgrade | 1,197,714 |

| Borča | 51,862 |

| Kaluđerica | 28,483 |

| Lazarevac | 27,635 |

| Obrenovac | 25,380 |

| Mladenovac | 22,346 |

| Surčin | 20,602 |

| Sremčica | 19,434 |

| Ugrinovci | 11,859 |

| Leštane | 10,454 |

| Ripanj | 10,084 |

Although there are several historic religious communities in Belgrade, the religious makeup of the city is relatively homogeneous. The Serbian Orthodox community is by far the largest, with 1,475,168 adherents. There are also 31,914 Muslims, 13,720 Roman Catholics, and 3,128 Protestants.

There once was a significant Jewish community in Belgrade but, following the World War II Nazi occupation of the city and subsequent Jewish emigration, their numbers have fallen from over 10,000 to just 295.[149] Belgrade also used to have one of the largest Buddhist colonies in Europe outside Russia when some 400 mostly Buddhist Kalmyks settled on the outskirts of Belgrade following the Russian Civil War. The first Buddhist temple in Europe was built in Belgrade in 1929. Most of them moved away after the World War II and their temple, Belgrade pagoda, was abandoned, claimed by the new Communist regime and eventually demolished.[150]

Economy

[edit]

Belgrade is the financial centre of Serbia and Southeast Europe, with a total of 17×106 m2 (180×106 sq ft) of office space.[151] It is also home to the country's Central Bank. 750,550 people are employed (July 2020)[152] in 120,286 companies,[153] 76,307 enterprises and 50,000 shops.[152][154] The City of Belgrade itself owns 267,147 m2 (2,875,550 sq ft) of rentable office space.[155]

As of 2019, Belgrade contained 31.4% of Serbia's employed population and generated over 40.4% of its GDP.[156][157][158] City GDP in 2023 at purchasing power parity is estimated at $73 bn USD, which is $43,400 per capita in terms of purchasing power parity. Nominal GDP in 2023 is estimated at $31.5 bn USD, which is $18.700 per capita.[159]

New Belgrade is the country's Central business district and one of Southeastern Europe's financial centres. It offers a range of facilities, such as hotels, congress halls (e.g. Sava Centar), Class A and B office buildings, and business parks (e.g. Airport City Belgrade). Over 1.2×106 m2 (13×106 sq ft) of land is under construction in New Belgrade, with the value of planned construction over the next three years estimated at over 1.5 billion euros. The Belgrade Stock Exchange is also located in New Belgrade.

With 6,924 companies in the IT sector (according to 2013 data[update]), Belgrade is one of the foremost information technology hubs in Southeast Europe.[153] Microsoft's Development Center Serbia, located in Belgrade, was, at the time of its establishment, the fifth such programme on the globe.[160] Many global IT companies choose Belgrade as their European or regional centre of operations, such as Asus,[161] Intel,[162] Dell,[163] Huawei, Nutanix,[164] NCR etc.[165] The most famous Belgrade IT startups, among others, are Nordeus, ComTrade Group, MicroE, FishingBooker, and Endava. IT facilities in the city include the Mihajlo Pupin Institute and the ILR,[166] as well as the brand-new IT Park Zvezdara.[167] Many prominent IT innovators began their careers in Belgrade, including Voja Antonić and Veselin Jevrosimović.

In December 2021, the average Belgrade monthly net salary stood at 94,463 RSD ($946) in net terms, with the gross equivalent at 128,509 RSD ($1288), while in New Belgrade CBD is Euros 1,059.[168] 88% of the city's households owned a computer, 89% had a broadband internet connection and 93% had pay television services.[169]

According to Cushman & Wakefield, Knez Mihajlova street is 36th most expensive retail street in the world in terms of renting commercial space.[170]

As an example of the attractiveness of the city and its importance in this part of the continent is the fact that numerous multinational companies choose precisely Belgrade to place its local headquarters. An early example of this was the multinational food-giant McDonald's opening its first ever restaurant in a communist country in Europe in Belgrade.[171]

Culture

[edit]

According to the BBC, Belgrade is one of the five most creative cities in the world.[172] Belgrade hosts many annual international cultural events, including the Film Festival, Theatre Festival, Summer Festival, BEMUS, Belgrade Early Music Festival, Book Fair, Belgrade Choir Festival, Eurovision Song Contest 2008, and the Beer Fest.[173] In 2022 Belgrade was also home to the Europride event, even though the Serbian president, Aleksandar Vučić, tried to cancel it.[174] The Nobel Prize winning author Ivo Andrić wrote his most famous work, The Bridge on the Drina, in Belgrade.[175] Other prominent Belgrade authors include Branislav Nušić, Miloš Crnjanski, Borislav Pekić, Milorad Pavić and Meša Selimović.[176][177][178] The most internationally prominent artists from Belgrade are Charles Simic, Marina Abramović and Milovan Destil Marković.

Most of Serbia's film industry is based in Belgrade. FEST is an annual film festival that has been held since 1971. Through 2013, the festival had been attended by four million people and had presented almost 4,000 films.[179]

The city was one of the main centres of the Yugoslav new wave in the 1980s: VIS Idoli, Ekatarina Velika, Šarlo Akrobata and Električni Orgazam were all from Belgrade. Other notable Belgrade rock acts include Riblja Čorba, Bajaga i Instruktori and Partibrejkers.[180][181] Today, it is the centre of the Serbian hip hop scene, with acts such as Beogradski Sindikat, Bad Copy, Škabo, Marčelo, and most of the Bassivity Music stable hailing from or living in the city.[182][183] There are numerous theatres, the most prominent of which are National Theatre, Theatre on Terazije, Yugoslav Drama Theatre, Zvezdara Theatre, and Atelier 212. The Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts is also based in Belgrade, as well as the National Library of Serbia. Other major libraries include the Belgrade City Library and the Belgrade University Library. Belgrade's two opera houses are: National Theatre and Madlenianum Opera House.[184][185] Following the victory of Serbia's representative Marija Šerifović at the Eurovision Song Contest 2007, Belgrade hosted the Contest in 2008.[186]

There are more than 1650 public sculptures in Belgrade.[187][188]

Museums

[edit]

The most prominent museum in Belgrade is the National Museum, founded in 1844 and reconstructed from 2003 until June 2018. The museum houses a collection of more than 400,000 exhibits (over 5600 paintings and 8400 drawings and prints, including many foreign masters like Bosch, Juan de Flandes, Titian, Tintoretto, Rubens, Cézanne, G.B. Tiepolo, Renoir, Monet, Lautrec, Matisse, Picasso, Gauguin, Chagall, Van Gogh, Mondrian etc.) and also the famous Miroslav's Gospel.[189] The Ethnographic Museum, established in 1901, contains more than 150,000 items showcasing the rural and urban culture of the Balkans, particularly the countries of former Yugoslavia.[190]

The Museum of Contemporary Art was the first contemporary art museum in Yugoslavia and one of the first museums of this type in the world.[191] Following its foundation in 1965, has amassed a collection of more than 8,000 works from art produced across the former Yugoslavia.[192] The museum was closed in 2007, but has since been reopened in 2017 to focus on the modern as well as on the Yugoslav art scenes.[193] Artist Marina Abramović, who was born in Belgrade, held an exhibition in the Museum of Contemporary Art, which the New York Times described as one of the most important cultural happenings in the world in 2019.[194][195] The exhibition was seen by almost 100,000 visitors. Marina Abramović made a stage speech and performance in front of 20,000 people.[196] In the heart of Belgrade you can also find the Museum of Applied Arts, a museum that has been awarded for the Institution of the Year 2016 by ICOM.[197]

The Military Museum, established in 1878 in Kalemegdan, houses a wide range of more than 25,000 military objects dating from the prehistoric to the medieval to the modern eras. Notable items include Turkish and oriental arms, national banners, and Yugoslav Partisan regalia.[198][199]

The Museum of Aviation in Belgrade located near Belgrade Nikola Tesla Airport has more than 200 aircraft, of which about 50 are on display, and a few of which are the only surviving examples of their type, such as the Fiat G.50. This museum also displays parts of shot down US and NATO aircraft, such as the F-117 and F-16.[200]

The Nikola Tesla Museum, founded in 1952, preserves the personal items of Nikola Tesla, the inventor after whom the Tesla unit was named. It holds around 160,000 original documents and around 5,700 personal other items including his urn.[201] The last of the major Belgrade museums is the Museum of Vuk and Dositej, which showcases the lives, work and legacy of Vuk Stefanović Karadžić and Dositej Obradović, the 19th century reformer of the Serbian literary language and the first Serbian Minister of Education, respectively.[202] Belgrade also houses the Museum of African Art, founded in 1977, which has a large collection of art from West Africa.[203]

With around 95,000 copies of national and international films, the Yugoslav Film Archive is the largest in the region and among the 10 largest archives in the world.[204] The institution also operates the Museum of Yugoslav Film Archive, with movie theatre and exhibition hall. The archive's long-standing storage problems were finally solved in 2007, when a new modern depository was opened.[205] The Yugoslav Film Archive also exhibits original Charlie Chaplin's stick and one of the first movies by Auguste and Louis Lumière.[206]

The Belgrade City Museum moved into a new building in downtown in 2006.[207] The museum hosts a range of collections covering the history of urban life since prehistory.[208] Belgrade City Museum also includes additional sites, such as Ivo Andrić Museum, Princess Ljubica's Residence, Paja Jovanović Museum, Jovan Cvijić Museum.[209] The Museum of Yugoslavia has collections from the Yugoslav era. Beside paintings, the most valuable are Moon rocks donated by Apollo 11 crew Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins while visiting Belgrade in 1969 and from mission Apollo 17 donated by Richard Nixon in 1971.[210] The museum also houses Joseph Stalin's sabre with 260 brilliants and diamonds, donated by Stalin himself.[211] The Museum of Science and Technology, founded in 1989, moved to the building of the first city's power plant in Dorćol in 2005.[212][213]

Architecture

[edit]

Belgrade has wildly varying architecture, from the centre of Zemun, typical of a Central European town,[214] to the more modern architecture and spacious layout of New Belgrade.

The oldest architecture is found in Kalemegdan Park. Outside of Kalemegdan, the oldest buildings date only from the 18th century, due to its geographic position and frequent wars and destructions.[215] The oldest public structure in Belgrade is a nondescript Turkish türbe, while the oldest house is a modest clay house on Dorćol, from late 18th century.[216] Western influence began in the 19th century, when the city completely transformed from an oriental town to the contemporary architecture of the time, with influences from neoclassicism, romanticism, and academic art. Serbian architects took over the development from foreign builders in the late 19th century, producing the National Theatre, Stari Dvor, Cathedral Church and later, in the early 20th century, the House of the National Assembly and National Museum, influenced by art nouveau.[215] Elements of Serbo-Byzantine Revival are present in buildings such as Vuk Foundation House, old Post Office in Kosovska street, and sacral architecture, such as St. Mark's Church (based on the Gračanica monastery), and the Church of Saint Sava.[215] In the socialist period, housing was built quickly and cheaply for the huge influx of people fleeing the countryside following World War II, sometimes resulting in the brutalist architecture of the blokovi ('blocks') of New Belgrade; a socrealism trend briefly ruled, resulting in buildings like the Trade Union Hall.[215] However, in the mid-1950s, modernist trends took over, and still dominate the Belgrade architecture.[215] Belgrade has the second oldest sewer system in Europe.[217] The Clinical Centre of Serbia spreads over 34 hectares and consists of about 50 buildings, while also has 3,150 beds considered to be the highest number in Europe,[218] and among highest in the world.[219]

Tourism

[edit]

Lying on the main artery connecting Europe and Asia, as well as, eventually, the Orient Express, Belgrade has been a popular place for travellers through the centuries. In 1843, on Dubrovačka Street (today Kralj Petar Street ), Serbia's knez Mihailo Obrenović built a large edifice which became the first hotel in Belgrade: Kod jelena ('at the deer's'), in the neighbourhood of Kosančićev Venac. Many criticised the move at the time due to the cost and the size of the building, but it soon became the gathering point of the Principality's wealthiest citizens. Colloquially, the building was also referred to as the staro zdanje, or the 'old edifice'. It remained a hotel until 1903 before being demolished in 1938.[220][221] After the staro zdanje, numerous hotels were built in the second half of the 19th century: Nacional and Grand, also in Kosančićev Venac, Srpski Kralj, Srpska Kruna, Grčka Kraljica near Kalemegdan, Balkan and Pariz in Terazije, London, etc.[222]

As Belgrade became connected via steamboats and railway (after 1884), the number of visitors grew and new hotels were opened with luxurious commodities. In Savamala, the hotels Bosna and Bristol were opened. Other hotels included Solun and Orient, which was built near the Financial Park. Tourists who arrived by the Orient Express mostly stayed at the Petrograd Hotel in Wilson Square. Hotel Srpski Kralj, at the corner of Uzun Mirkova and Pariska Streets was considered the best hotel in Belgrade during the Interbellum. It was destroyed during World War II.[222]

The historic areas and buildings of Belgrade are among the city's premier attractions. They include Skadarlija, the National Museum and adjacent National Theatre, Zemun, Nikola Pašić Square, Terazije, Students' Square, the Kalemegdan Fortress, Knez Mihailova Street, the Parliament, the Church of Saint Sava, and the Old Palace. On top of this, there are many parks, monuments, museums, cafés, restaurants and shops on both sides of the river. The hilltop Avala Monument and Avala Tower offer views over the city. According to The Guardian, Dorcol is the one of top ten coolest suburbs in Europe.[223] The elite neighbourhood of Dedinje is situated near the Topčider and Košutnjak parks. The Dedinje Royal Compound which houses the former royal residences of (Kraljevski Dvor and Beli Dvor) is open for visitors. The palace has many valuable artworks.[224] Nearby, Josip Broz Tito's mausoleum, called The House of Flowers, documents the life of the former Yugoslav president.

Ada Ciganlija is a former island on the Sava River, and Belgrade's biggest sports and recreational complex. Today it is connected with the right bank of the Sava via two causeways, creating an artificial lake. It is the most popular destination for Belgraders during the city's hot summers. There are 7 km (4 mi) of long beaches and sports facilities for various sports including golf, football, basketball, volleyball, rugby union, baseball, and tennis.[225] During summer there are between 200,000 and 300,000 bathers daily.[226]

Extreme sports are available, such as bungee jumping, water skiing, and paintballing.[225][227] There are numerous trails on the island, where it is possible to ride a bike, go for a walk, or go jogging.[225][227] Apart from Ada, Belgrade has total of 16 islands[228] on the rivers, many still unused. Among them, the Great War Island, at the confluence of Sava, stands out as an oasis of unshattered wildlife (especially birds).[229] These areas, along with nearby Small War Island, are protected by the city's government as a nature preserve.[230] There are 37 protected natural resources in the Belgrade urban area, among which eight are geo-heritage sites, i.e. Straževica profile, Mašin Majdan-Topčider, Profile at the Kalemegdan Fortress, Abandoned quarry in Barajevo, Karagača valley, Artesian well in Ovča, Kapela loess profile, and Lake in Sremčica. Other 29 places are biodiversity sites.[231]

Tourist income in 2016 amounted to nearly half a billion euros;[232] with a visit of almost a million registered tourists.[233] Of those, in 2019 more than 100,000 tourists arrived by 742 river cruisers.[233][234] Average annual growth is between 13% and 14%.[233]

As of 2018, there are three officially designated camp grounds in Belgrade. The oldest one is located in Batajnica, along the Batajnica Road. Named "Dunav", it is one of the most visited campsites in the country. The second one is situated within the complex of the ethno-household "Zornić's House" in the village of Baćevac, while the third is located in Ripanj, on the slopes of Avala mountain. In 2017 some 15,000 overnights were recorded in camps.[235]

Belgrade is a common stop on the Rivers Route, European cycling route known as "Danube Bike Trail" in Serbia as well as on the Sultans Trail, a long-distance hiking footpath between Vienna and Istanbul.

Nightlife

[edit]Belgrade has a reputation for vibrant nightlife; many clubs that are open until dawn can be found throughout the city.[236] The most recognisable nightlife features of Belgrade are the barges (splav) spread along the banks of the Sava and Danube Rivers.[237][238][239]

Many weekend visitors—particularly from Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Slovenia—prefer Belgrade nightlife to that of their own capitals due to its perceived friendly atmosphere, plentiful clubs and bars, cheap drinks, lack of significant language barriers, and a lack of night life regulation.[240][241] One of the most famous sites for alternative cultural happenings in the city is the SKC (Student Cultural Centre), located right across from Belgrade's highrise landmark, the Belgrade Palace tower. Concerts featuring famous local and foreign bands are often held at the centre. SKC is also the site of various art exhibitions, as well as public debates and discussions.[242]

A more traditional Serbian nightlife experience, accompanied by traditional music known as Starogradska (roughly translated as Old Town Music), typical of northern Serbia's urban environments, is most prominent in Skadarlija, the city's old bohemian neighbourhood where the poets and artists of Belgrade gathered in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Skadar Street (the centre of Skadarlija) and the surrounding neighbourhood are lined with some of Belgrade's best and oldest traditional restaurants (called kafanas in Serbian), which date back to that period.[243] At one end of the neighbourhood stands Belgrade's oldest beer brewery, founded in the first half of the 19th century.[244] One of the city's oldest kafanas is the Znak pitanja ('?').[245]

The Times reported that Europe's best nightlife can be found in Belgrade.[246] In the Lonely Planet 1000 Ultimate Experiences Guide of 2009, Belgrade was placed at the 1st spot among the top 10 party cities in the world.[247]

Sport and recreation

[edit]

There are approximately one-thousand sports facilities in Belgrade, many of which are capable of serving all levels of sporting events.[248]

Ada Ciganlija island, with its lake and beaches, is one of the most important recreational areas in the city. With a total of 8 km beaches, and a variety of bars, cafés, restaurants and sport facilities, Ada Ciganlija attracts many visitors, especially in summertime.

Košutnjak Park Forest has numerous running and bike trails, sports facilities for a variety of sports, and indoor and outdoor pools. It is a popular destination that is located only 2 km from Ada Ciganlija.

During the 1960s and 1970s Belgrade held a number of major international events such as the first ever World Aquatics Championships in 1973, 1976 European Football Championship and 1973 European Cup Final, European Athletics Championships in 1962 and European Indoor Games in 1969, European Basketball Championships in 1961 and 1975, European Volleyball Championship for men and women in 1975 and World Amateur Boxing Championships in 1978.

Since the early 2000s Belgrade again hosts major sporting events nearly every year. Some of these include EuroBasket 2005, European Handball Championship (men's and women's) in 2012, World Handball Championship for women in 2013, European Volleyball Championships for men in 2005 for men and 2011 for women, the 2006 and 2016 European Water Polo Championship, the European Youth Olympic Festival 2007 and the 2009 Summer Universiade.[249] More recently, Belgrade hosted European Athletics Indoor Championships in 2017 and the basketball EuroLeague Final Four tournaments in 2018 and 2022. Global and continental championships in other sports such as tennis, futsal, judo, karate, wrestling, rowing, kickboxing, table tennis, and chess have also been held in recent years.

The city is home to Serbia's two biggest and most successful football clubs, Red Star Belgrade and Partizan Belgrade. Red Star won the UEFA Champions League (European Cup) in 1991, and Partizan was runner-up in 1966. The two major stadiums in Belgrade are Marakana (Red Star Stadium) and Partizan Stadium.[250] The Eternal derby is between Red Star and Partizan.

With a capacity of 19,384 spectators,Belgrade Arena is one of the largest indoor arenas in Europe.[251] It is used for major sporting events and large concerts. In May 2008, it was the venue for the 53rd Eurovision Song Contest.[252]Aleksandar Nikolić Hall is the main venue of basketball clubs KK Partizan, the European champion of 1992, and KK Crvena Zvezda.[253][254] In recent years, Belgrade has also given rise to several world-class tennis players such as Ana Ivanovic, Jelena Janković and Novak Djokovic. Ivanovic and Djokovic are the first female and male Belgraders, respectively, to win Grand Slam singles titles and been ATP number 1 with Jelena Janković. The Serbian national team won the 2010 Davis Cup, beating the French team in the finals played in the Belgrade Arena.[255]

The Belgrade Marathon is held annually since 1988. Belgrade was a candidate to host the 1992 and the 1996 Summer Olympic Games.[256][257]

Fashion and design

[edit]Since 1996,[258] semiannual (autumn/winter and spring/summer seasons) fashion weeks are held citywide. Numerous Serbian and foreign designers and fashion brands have their shows during Belgrade Fashion Week. The festival, which collaborates with London Fashion Week, has helped launch the international careers of local talents such as George Styler and Ana Ljubinković. British fashion designer Roksanda Ilincic, who was born in the city, also frequently presents her runway shows in Belgrade.

In addition to fashion, there are two major design shows held in Belgrade every year which attract international architects and industrial designers such as Karim Rashid, Daniel Libeskind, Patricia Urquiola, and Konstantin Grcic. Both the Mikser Festival and Belgrade Design Week feature lectures, exhibits and competitions. Furthermore, international designers like Sacha Lakic, Ana Kraš, Bojana Sentaler, and Marek Djordjevic are originally from Belgrade.

Media

[edit]

Belgrade is the most important media hub in Serbia. The city is home to the main headquarters of the national broadcaster Radio Television Serbia (RTS), which is a public service broadcaster.[259] The most popular commercial broadcaster is RTV Pink, a Serbian media multinational, known for its popular entertainment programmes. One of the most popular commercial broadcasters is B92, another media company, which has its own TV station, radio station, and music and book publishing arms, as well as the most popular website on the Serbian internet.[260][261] Other TV stations broadcasting from Belgrade include 1Prva (formerly Fox televizija), Nova, N1 and others which only cover the greater Belgrade municipal area, such as Studio B.

High-circulation daily newspapers published in Belgrade include Politika, Blic, Alo!, Kurir and Danas. There are two sporting dailies, Sportski žurnal and Sport, and one economic daily, Privredni pregled. A new free distribution daily, 24 sata, was founded in the autumn of 2006. Also, Serbian editions of licensed magazines such as Harper's Bazaar, Elle, Cosmopolitan, National Geographic, Men's Health, Grazia and others have their headquarters in the city.

Education

[edit]

Belgrade has two state universities and several private institutions of higher education. The University of Belgrade, founded in 1808 as a grande école, is the oldest institution of higher learning in Serbia.[262] Having developed with much of the rest of the city in the 19th century, several university buildings are recognised as forming a constituent part of Belgrade's architecture and cultural heritage. With enrolment numbers of nearly 90,000 students, the university is one of Europe's largest.[263]

The city is also home to 195 primary (elementary) schools and 85 secondary schools. The primary school system has 162 regular schools, 14 special schools, 15 art schools, and 4 adult schools, while the secondary school system has 51 vocational schools, 21 gymnasiums, 8 art schools and 5 special schools. The 230,000 pupils are managed by 22,000 employees in over 500 buildings, covering around 1.1×106 m2 (12×106 sq ft).[264]

Transportation

[edit]

Belgrade has an extensive public transport system consisting of buses (118 urban lines and more than 300 suburban lines), trams (12 lines), trolleybuses (8 lines) and S-Train BG Voz (6 lines).[265][266] Buses, trolleybuses and trams are run by GSP Beograd and SP Lasta in cooperation with private companies on some bus routes. The S-train network, BG Voz, run by city government in cooperation with Serbian Railways, is a part of the integrated transport system, and has three lines (Batajnica-Ovča and Ovča-Resnik and Belgrade centre-Mladenovac), with more announced.[267][268] As of 27 February 2024[update] tickets may be purchased either via SMS or in physical paper form via the Beograd plus / Београд плус system.[269] Daily connections link the capital to other towns in Serbia and many other European destinations through the city's central bus station. Since January 2025 all public transport in Belgrade is free.[270]

Beovoz was the suburban/commuter railway network that provided mass-transit services in the city, similar to Paris's RER and Toronto's GO Transit. The main usage of system was to connect the suburbs with the city centre. Beovoz was operated by Serbian Railways.[271] However, this system was abolished back in 2013, mostly due to introduction of more efficient BG Voz. Belgrade is one of the last big European capitals and cities with over a million people to have no metro or subway or other rapid transit system. As of November 2021, the Belgrade Metro is currently under construction, which will have 2 lines. The first line is expected to be operational by August 2028.[272][273]

The new Belgrade Centre railway station is the hub for almost all national and international trains. The high-speed rail that connects Belgrade with Novi Sad started its service on 19 March 2022.[274] The extension towards Subotica and Budapest is under construction,[275] and there are plans for a southwards extension towards Niš and North Macedonia.[276]

The city is placed along the Pan-European corridors X and VII.[10] The motorway system provides for easy access to Novi Sad and Budapest to the north, Niš to the south, and Zagreb to the west. Expressway is also toward Pančevo and new Expressway construction toward Obrenovac (Montenegro) is scheduled for March 2017. Belgrade bypass is connecting the E70 and E75 motorways and is under construction.[277]

Situated at the confluence of two major rivers, the Danube and the Sava, Belgrade has 11 bridges, the most important of which are Branko's Bridge, Ada Bridge, Pupin Bridge and Gazela Bridge, the last two of which connect the core of the city to New Belgrade. In addition, an 'inner magistral semi-ring' is almost done and includes a new Ada bridge across the Sava river and a new Pupin bridge across the Danube river, which ease commuting within the city and unload traffic from the Gazela Bridge and Branko's Bridge.[278]

The Port of Belgrade is on the Danube, and allows the city to receive goods by river.[279] The city is also served by Belgrade Nikola Tesla Airport, 12 km (7.5 mi) west of the city centre, near Surčin. At its peak in 1986, almost 3 million passengers travelled through the airport, though that number dwindled to a trickle in the 1990s.[280] Following renewed growth in 2000, the number of passengers reached approximately 2 million in 2004 and 2005,[281] over 2.6 million passengers in 2008,[282] reaching over 3 million passengers.[283] A record with over 4 million passengers was broken in 2014, when Belgrade Nikola Tesla Airport became the second fastest growing major airport in Europe.[284] The numbers continued to grow steadily and the all-time peak of over 6 million passengers was reached in 2019.[285]

International relations

[edit]Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]

List of Belgrade's sister and twin cities:[286]

Coventry, UK, since 1957[287][288]

Coventry, UK, since 1957[287][288] Chicago, US, since 2005

Chicago, US, since 2005 Ljubljana, Slovenia, since 2010[289][290]

Ljubljana, Slovenia, since 2010[289][290] Skopje, North Macedonia, since 2012[291][292]

Skopje, North Macedonia, since 2012[291][292] Caruaru, Brazil, since 2010

Caruaru, Brazil, since 2010 Shanghai, China, since 2018[293]

Shanghai, China, since 2018[293] Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina, since 2020[294]

Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina, since 2020[294]

Partner cities

[edit]Other friendships and cooperations, protocols, memorandums:[286]

Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, since 2018, Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation

Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, since 2018, Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation Rabat, Morocco, since 2017, Partnership and Cooperation Agreement

Rabat, Morocco, since 2017, Partnership and Cooperation Agreement Seoul, South Korea, since 2017, Memorandum of Understanding on Friendly Exchanges and Cooperation

Seoul, South Korea, since 2017, Memorandum of Understanding on Friendly Exchanges and Cooperation Astana, Kazakhstan, since 2016, Agreement on Cooperation[295]

Astana, Kazakhstan, since 2016, Agreement on Cooperation[295] Tehran, Iran, since 2016, Agreement on Cooperation[296]

Tehran, Iran, since 2016, Agreement on Cooperation[296] Corfu, Greece, since 2010, Protocol on Cooperation

Corfu, Greece, since 2010, Protocol on Cooperation Shenzhen, China, since 2009, Agreement on Cooperation[297]

Shenzhen, China, since 2009, Agreement on Cooperation[297] Zagreb, Croatia, since 2003, Letter of Intent

Zagreb, Croatia, since 2003, Letter of Intent Kyiv, Ukraine, since 2002, Agreement on Cooperation

Kyiv, Ukraine, since 2002, Agreement on Cooperation Algiers, Algeria, since 1991 declaration of mutual interests

Algiers, Algeria, since 1991 declaration of mutual interests Tel Aviv, Israel, since 1990, Agreement on Cooperation

Tel Aviv, Israel, since 1990, Agreement on Cooperation Bucharest, Romania, since 1999, Agreement on Cooperation

Bucharest, Romania, since 1999, Agreement on Cooperation Beijing, China, since 1980, Agreement on Cooperation[298]

Beijing, China, since 1980, Agreement on Cooperation[298] Rome, Italy, since 1971, Agreement on Friendship and Cooperation

Rome, Italy, since 1971, Agreement on Friendship and Cooperation Athens, Greece, since 1966, Agreement on Friendship and Cooperation

Athens, Greece, since 1966, Agreement on Friendship and Cooperation

Some of the city's municipalities are also twinned to small cities or districts of other big cities; for details see their respective articles.

Belgrade has received various domestic and international honours, including the French Légion d'honneur (proclaimed 21 December 1920; Belgrade is one of four cities outside France, alongside Liège, Luxembourg and Volgograd, to receive this honour), the Czechoslovak War Cross (awarded 8 October 1925), the Yugoslavian Order of the Karađorđe's Star (awarded 18 May 1939) and the Yugoslavian Order of the People's Hero (proclaimed on 20 October 1974, the 30th anniversary of the overthrow of Nazi German occupation during World War II).[299] All of these decorations were received for the war efforts during World War I and World War II.[300] In 2006, Financial Times' magazine Foreign Direct Investment awarded Belgrade the title of City of the Future of Southern Europe.[301][302]

See also

[edit]- List of people from Belgrade

- List of cities and towns on Danube river

- List of metropolitan areas in Europe

Notes

[edit]- ^ Yugoslavia was first named so with the 1929 constitutional changes. The country collapsed by 1992, at which point the polity called the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia persisted under the name until its renaming to Serbia and Montenegro in 2003, and dissolution in 2006.

References

[edit]- ^ Ethnicity - data by municipalities and cities (PDF). Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, Belgrade. 2023. p. 38. ISBN 978-86-6161-228-2.

- ^ "Ancient Period". City of Belgrade. 5 October 2000. Archived from the original on 16 February 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- ^ a b c Statistički godišnjak Beograda (PDF). Zavod za statistiku grada Beograda. ISSN 0585-1912. Retrieved 10 March 2024.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "First results of the 2022 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings". stat.gov.rs. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ Ethnicity – data by municipalities and cities (PDF). Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, Belgrade. 2023. p. 30. ISBN 978-86-6161-228-2.

- ^ Ковачевић, Миладин. "Регионални бруто домаћи производ, 2022" (PDF). Radni Dokument. Republički zavod za statistiku Srbije. ISSN 1820-0141. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI – Subnational HDI – Global Data Lab". globaldatalab.org. Archived from the original on 14 March 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ "Belgrade". Collins English Dictionary (13th ed.). HarperCollins. 2018. ISBN 978-0-008-28437-4.

- ^ "Definition of Belgrade | Dictionary.com". www.dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Why invest in Belgrade?". City of Belgrade. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Discover Belgrade". City of Belgrade. Archived from the original on 18 May 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ a b Rich, John (1992). The City in Late Antiquity. CRC Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-203-13016-2. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "The History of Belgrade". BelgradeNet Travel Guide. Archived from the original on 30 December 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ a b Nurden, Robert (22 March 2009). "Belgrade has risen from the ashes to become the Balkans' party city". Independent. London. Archived from the original on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ a b "Assembly of the City of Belgrade". City of Belgrade. Archived from the original on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- ^ "The World According to GAWC 2012". GAWC. Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ^ "About". Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- ^ Saric, J. (2008). "Paleolithic and mesolithic finds from profile of the Zemun loess". Starinar (58): 9–27. doi:10.2298/STA0858009S.

- ^ Chapman, John (2000). Fragmentation in Archaeology: People, Places, and Broken Objects. London: Routledge. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-415-15803-9.

- ^ Chapman, John (1981). The Vinča culture of south-east Europe: Studies in chronology, economy and society (2 vols). BAR International Series. Vol. 117. Oxford: BAR. ISBN 0-86054-139-8.

- ^ Radivojević, M.; Rehren, T.; Pernicka, E.; Šljivar, D. A.; Brauns, M.; Borić, D. A. (2010). "On the origins of extractive metallurgy: New evidence from Europe". Journal of Archaeological Science. 37 (11): 2775. Bibcode:2010JArSc..37.2775R. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2010.06.012.

- ^ Haarmann, Harald (2002). Geschichte der Schrift (in German). C.H. Beck. p. 20. ISBN 978-3-406-47998-4.

- ^ Mikić, Radivoje, ed. (2006). Српска породична енциклопедија, књига 3, Ба-Би [Serbian family encynclopedia, Vol. 3, Ba-Bi]. Narodna Knjiga, Politika. p. 116. ISBN 86-331-2732-6.

- ^ Belgrade A Cultural History. Oxford University Press. 29 October 2008. ISBN 9780199704521. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ "Jason and the Argonauts sail again". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ "Belgrade Fortress history". Public Enterprise "Belgrade Fortress". Archived from the original on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ^ "Constantine I – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 18 June 2008. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ "Philologic Results-". The ARTFL Project. Archived from the original on 13 August 2007. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ "History (Ancient Period)". Beograd.rs. Archived from the original on 16 February 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- ^ "City of Belgrade – Ancient Period". Beograd.rs. 5 October 2000. Archived from the original on 16 February 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2009.