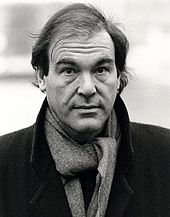

Oliver Stone

Oliver Stone | |

|---|---|

Stone in 2016 | |

| Born | William Oliver Stone[citation needed] September 15, 1946 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Yale University New York University (BFA) |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1971–present |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 3, including Sean Stone |

| Awards | Full list |

William Oliver Stone (born September 15, 1946) is an American filmmaker.[1][2][3] Stone is an acclaimed director, tackling subjects ranging from the Vietnam War, and American politics to musical biopics and crime dramas. He has received numerous accolades including three Academy Awards, a BAFTA Award, a Primetime Emmy Award, and five Golden Globe Awards.

Stone was born in New York City and later briefly attended Yale University. In 1967, Stone enlisted in the United States Army during the Vietnam War. He then served from 1967 to 1968 in the 25th Infantry Division and was twice wounded in action. For his service, he received military honors including a Bronze Star with "V" Device for valor, Purple Heart with Oak Leaf Cluster (to denote two wounds), an Air Medal and the Combat Infantryman Badge. His service in Vietnam would be the basis for his later career as a filmmaker in depicting the brutality of war.

Stone started his film career writing the screenplays for Midnight Express (1978), for which he won the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay; Conan the Barbarian (1982); and Scarface (1983). He then rose to prominence as writer and director of the Vietnam War film dramas Platoon (1986) and Born on the Fourth of July (1989), receiving Academy Awards for Best Director for both films, the former of which also won Best Picture. He also directed Salvador (1986), Wall Street (1987) and its sequel Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps (2010), The Doors (1991), JFK (1991), Heaven & Earth (1993), Natural Born Killers (1994), Nixon (1995), Any Given Sunday (1999), W. (2008) and Snowden (2016).

Many of Stone's films focus on controversial American political issues during the late 20th century, and as such were considered contentious at the times of their releases. Stone has been critical of the American foreign policy, which he considers to be driven by nationalist and imperialist agendas. He has approved of politicians Hugo Chávez and Vladimir Putin, the latter of whom was the subject of The Putin Interviews (2017).[4] Like his subject matter, Stone is a controversial figure in American filmmaking, with some critics accusing him of promoting conspiracy theories.[5][6][7][8][9]

Early life

[edit]Stone was born in New York City, the son of a French woman named Jacqueline (née Goddet)[10] and Louis Stone (born Abraham Louis Silverstein), a stockbroker.[11] He grew up in Manhattan and Stamford, Connecticut. His parents met in Paris during World War II where his father, a U.S. Army colonel, served as a financial officer on General Eisenhower's staff.[12][13] Stone's American-born father was Jewish, whereas his French-born mother was Roman Catholic, both non-practicing.[14] Stone was raised in the Episcopal Church,[15][16] and now practices Buddhism.[17]

Stone attended Trinity School in New York City before his parents sent him away to The Hill School, a college-preparatory school in Pottstown, Pennsylvania. His parents divorced abruptly while he was away at school (1962) and this, because he was an only child, marked him deeply. Stone's mother was often absent and his father made a big impact on his life—perhaps because of this, father-son relationships feature heavily in Stone's films.[18]

He often spent parts of his summer vacations with his maternal grandparents in France, both in Paris and La Ferté-sous-Jouarre in Seine-et-Marne. Stone also worked at 17 in the Paris mercantile exchange in sugar and cocoa – a job that proved inspirational to Stone for his film Wall Street. He speaks French fluently.[19] Stone graduated from The Hill School in 1964.

Stone was admitted to Yale University, but left in June 1965 at age 18[12][20] to teach high school students English for six months in Saigon at the Free Pacific Institute in South Vietnam.[21] Afterwards, he worked for a short while as a wiper on a United States Merchant Marine ship in 1966, traveling from Asia to the US across the rough Pacific Ocean in January.[22] He returned to Yale, where he dropped out a second time (in part due to working on an autobiographical novel, "A Child's Night Dream," published in 1997 by St. Martin's Press).[23]

U.S. Army

[edit]In April 1967, Stone enlisted in the United States Army and requested combat duty in Vietnam. From September 27, 1967, to February 23, 1968, he served in Vietnam with 2nd Platoon, B Company, 3rd Battalion, 22nd Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division. Stone was first wounded in action in late 1967, when he was shot in the neck during a night ambush. On January 15, 1968, he was wounded again when the shrapnel from a detonated satchel charge implanted in a tree penetrated his legs and buttocks.[24] Following his recovery, he briefly served transitional duty as a military policeman in Saigon. He was then transferred to the 1st Cavalry Division participating in long-range reconnaissance patrols before being transferred again to the 9th Cavalry Regiment until November 1968. On August 21, 1968, Stone charged and killed a North Vietnamese sniper who had several squads pinned down during a firefight. For that action, he was awarded the Bronze Star with "V" Device for "heroism in ground combat."[25][26]

In addition to the Bronze Star, his military awards include the Purple Heart with Oak Leaf Cluster to denote two awards, the Air Medal, the Army Commendation Medal, Sharpshooter Badge with Rifle Bar, Marksman Badge with Auto Rifle Bar, the National Defense Service Medal, the Vietnam Service Medal with one Silver Service Star, the Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross with Unit Citation with Palm, two Overseas Service Bars, the Vietnam Campaign Medal and the Combat Infantryman Badge.[27]

After the war

[edit]On June 30 1969, the French news program Voila interviewed a then-unknown Stone while filming "on the street" interviews about the war in Central Park. In fluent French, he told them, "My name is Oliver Stone, I’m 22 years old, I’m from New York, and my mother is French from Paris. I served in Vietnam with the American Army for 15 months and I returned to the United States six months ago. It changed me. It changes a lot of boys." He added that drug use was rampant among American soldiers.[28] Following the war, Stone suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder.[29] He also experienced health issues he believes were caused by Agent Orange exposure, as well as combat induced hearing loss and tinnitus.[30][31] In 2024, Stone commemorated the 50th anniversary of the Vietnam War's conclusion by sharing his reflections during panel discussions at the Harvard Institute of Politics[32] and San Diego State University's Center for War and Society.[33]

| |||

On July 4, 2024, Stone was awarded the rank of Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters, the highest civilian honor in France, for cultural contributions to both the country and the film industry.[34] He was previously awarded the rank of Chevalier in 1992.

Writing and directing career

[edit]1970s

[edit]Stone graduated from New York University with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in film in 1971, where his teachers included director and fellow NYU alumnus Martin Scorsese.[35] The same year, he had a small acting role in the comedy The Battle of Love's Return.[36] Stone made a short, well received 12-minute film Last Year in Viet Nam. He worked as a taxi driver, film production assistant, messenger, and salesman before making his mark in film as a screenwriter in the late 1970s, in the period between his first two films as a director: horror films Seizure and The Hand.

In 1979, Stone was awarded his first Oscar, after adapting true-life prison story Midnight Express into the successful film of the same name for British director Alan Parker (the two men would later collaborate on the 1996 movie of stage musical Evita). The original author, Billy Hayes, around whom the film is set, said the film's depiction of prison conditions was accurate. Hayes said that the "message of 'Midnight Express' isn't 'Don't go to Turkey. It's 'Don't be an idiot like I was, and try to smuggle drugs.' "[37] Stone later apologized to Turkey for over-dramatizing the script, while standing by the film's stark depiction of the brutality of Turkish prisons.[38]

1980s

[edit]

Stone wrote further features, including Brian De Palma's drug lord epic Scarface, loosely inspired by his own addiction to cocaine, which he successfully kicked while working on the screenplay.[39] He also penned Year of the Dragon (co-written with Michael Cimino) featuring Mickey Rourke, before his career took off as a writer-director in 1986. Like his contemporary Michael Mann, Stone is unusual in having written or co-written most of the films he has directed. In 1986, Stone directed two films back to back: the critically acclaimed but commercially unsuccessful Salvador, shot largely in Mexico, and his long in-development Vietnam project Platoon, shot in the Philippines.

Platoon brought Stone's name to a much wider audience. It also finally kickstarted a busy directing career, which saw him making nine films over the next decade. Platoon won many rave reviews (Roger Ebert later called it the ninth best film of the 1980s), large audiences, and Academy Awards for Best Picture and Best Director. In 2007, a film industry vote ranked it at number 83 in an American Film Institute "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movies" poll of the previous century's best American movies. British TV channel Channel 4 voted Platoon as the sixth greatest war film ever made.[40] In 2019, Platoon was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the United States National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[41]

Platoon was the first of three films Stone has made about the Vietnam War: the others were Born on the Fourth of July and Heaven & Earth, each dealing with different aspects of the war. Platoon is a semi-autobiographical film about Stone's experience in combat; Born on the Fourth of July is based on the autobiography of US Marine turned peace campaigner Ron Kovic; Heaven & Earth is based on the memoir When Heaven and Earth Changed Places, in which Le Ly Hayslip recalls her life as a Vietnamese village girl drastically affected by the war and who finds another life in the USA.

Following the success of Platoon, Stone directed another hit, 1987's Wall Street, starring Charlie Sheen and Michael Douglas. Lead performer Michael Douglas received an Academy Award for Best Actor for his role as a ruthless Wall Street corporate raider. After Wall Street, he directed another movie the following year: Talk Radio, based on Eric Bogosian's Pulitzer-nominated play.

1990s

[edit]The Doors, released in 1991, received criticism from former Doors keyboardist Ray Manzarek during a question-and-answer session at Indiana University East in 1997. During the discussion, Manzarek stated that he sat down with Stone about The Doors and Jim Morrison for over 12 hours. Patricia Kennealy-Morrison—a rock critic and author—was a consultant on the movie, in which she makes a cameo appearance, but she writes in her memoir Strange Days: My Life With and Without Jim Morrison (Dutton, 1992) that Stone ignored everything she told him and proceeded with his own version of events. From the moment the movie was released, she blasted it as untruthful and inaccurate.[42] The other surviving former members of the band, John Densmore and Robby Krieger, also cooperated with the filming of The Doors, but Krieger distanced himself from the work before the film's release. However, Densmore thought highly of the film,[43] and celebrated its DVD release on a panel with Oliver Stone.

During this same period, Stone directed one of his most ambitious, controversial and successful films: JFK, depicting the assassination of John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963. In 1991, Stone showed JFK to Congress on Capitol Hill, which helped lead to passage of the Assassination Materials Disclosure Act[44] of 1992. The Assassination Records Review Board (created by Congress to lessen, but not end the secrecy surrounding Kennedy's assassination) discussed the film, including Stone's observation at the end of the film, about the dangers inherent in government secrecy.[45] Stone published an annotated version of the screenplay, in which he cites references for his claims, shortly after the film's release. He stated: "I make my films like you're going to die if you miss the next minute. You better not go get popcorn."[46]

In 1994, Stone directed Natural Born Killers, a violent crime film intended to satirize the modern media. The film had originally been based on a screenplay by Quentin Tarantino, but it underwent significant rewriting by Stone, Richard Rutowski, and David Veloz.[47] Before it was released, the MPAA gave the film a NC-17 rating; this caused Stone to cut four minutes of film footage in order to obtain an R rating (he eventually released the unrated version on VHS and DVD in 2001). The film was the recipient of the Grand Special Jury Prize at the Venice Film Festival[48] that year. He appeared in a cameo as himself in the presidential comedy Dave.

Stone went on to direct the 1995 Richard Nixon biopic Nixon, which received multiple Oscar nominations for: the script, John Williams' score, Joan Allen as Pat Nixon, and Anthony Hopkins' portrait of the title role. Stone followed Nixon with the 1997 road movie/film noir, U Turn, then 1999's Any Given Sunday, a film about power struggles within an American football team.

2000s

[edit]

After a period spanning 13 years (1986 to 1999), where he released a new film every 1–2 years, Stone slowed his pace to 4 movies and 2 documentaries in the ensuing decade. First directing Alexander in 2004, then World Trade Center in 2006, followed by W. in 2008, and finally South of the Border (Documentary) 2009.

Stone directed Alexander. He later re-edited his biographical film of Alexander the Great into a two-part, 3-hour 37-minute film Alexander Revisited: The Final Cut, which became one of the highest-selling catalog items from Warner Bros.[49] He further refined the film and in 2014 released the two-part, 3-hour 26-minute Alexander: The Ultimate Cut. After Alexander, Stone went on to direct World Trade Center, based on the true story of two PAPD policemen who were trapped in the rubble and survived the September 11 attacks.

Stone wrote and directed the George W. Bush biopic W., chronicling the former president's: childhood, relationship with his father, struggles with alcoholism, rediscovery of his Christian faith, and continues the rest of his life up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

2010s

[edit]

In 2010, Stone returned to the theme of Wall Street for the sequel Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps.[50]

In 2012, Stone directed Savages, based on a novel by Don Winslow.

In 2015, he was presented with an honorific award at the Sitges Film Festival for his film, Snowden, starring Joseph Gordon-Levitt as whistleblower Edward Snowden. Snowden finished filming in May 2015 and was released on September 16, 2016. He received the 2017 Cinema for Peace Award for Justice for such film.

On May 22, 2017, various industry papers reported that Stone was going to direct a television series about the Guantanamo detention camp.[51][52][53][54] Daniel Voll was credited with creating the series. Harvey Weinstein's production company was reported as financing the series, with Stone scheduled to direct every episode of the first season[citation needed]. However, Stone announced he would quit the series after sexual misconduct allegations surfaced against Weinstein in October 2017.[55]

2020s

[edit]In July 2020, Stone teamed with Houghton Mifflin Harcourt to release his first memoir, titled Chasing the Light: Writing, Directing, and Surviving Platoon, Midnight Express, Scarface, Salvador, and the Movie Game, which chronicles his turbulent upbringing in New York City, volunteering for combat in Vietnam, and the trials and triumphs of moviemaking in the 1970s and '80s. The book, which ends on his Oscar-winning Platoon, was praised by The New York Times: "The Oliver Stone depicted in these pages — vulnerable, introspective, stubbornly tenacious and frequently heartbroken—may just be the most sympathetic character he's ever written... neatly sets the stage for the possibility of that rarest of Stone productions: a sequel."[56] In 2024, he announced that he was writing a follow-up memoir for Simon & Schuster. [57]

Documentaries

[edit]

Stone made three documentaries on Fidel Castro: Comandante (2003), Looking for Fidel, and Castro in Winter (2012). He made Persona Non Grata, a documentary on Israeli-Palestinian relations, interviewing several notable figures of Israel, including Ehud Barak, Benjamin Netanyahu and Shimon Peres, as well as Yasser Arafat, leader of the Palestine Liberation Organization.

In 2009, Stone completed a feature-length documentary, South of the Border about the rise of leftist governments in Latin America, featuring seven presidents: Hugo Chávez of Venezuela, Bolivia's Evo Morales, Ecuador's Rafael Correa, Cuba's Raúl Castro, the Kirchners of Argentina, Brazil's Lula da Silva, and Paraguay's Fernando Lugo, all of whom are critical of US foreign policy in South America. Stone hoped the film would get the rest of the Western world to rethink socialist policies in South America, particularly as it was being applied by Venezuela's Hugo Chávez. Chávez joined Stone for the premiere of the documentary at the Venice International Film Festival in September 2009.[58] Stone defended his decision not to interview Chávez's opponents, stating that oppositional statements and TV clips were scattered through the documentary and that the documentary was an attempt to right a balance of heavily negative coverage. He praised Chávez as a leader of the Bolivarian Revolution, a movement for social transformation in Latin America, and also praised the six other presidents in the film. The documentary was also released in several cities in the United States and Europe in the mid-2010.[59][60]

In 2012, the documentary miniseries Oliver Stone's Untold History of the United States premiered on Showtime, Stone co-wrote, directed, produced, and narrated the series, having worked on it since 2008 with co-writers American University historian Peter J. Kuznick and British screenwriter Matt Graham.[61] The 10-part series is supplemented by a 750-page companion book of the same name, also written by Stone and Kuznick, published on October 30, 2012, by Simon & Schuster.[62] Stone described the project as "the most ambitious thing I've ever done. Certainly in documentary form, and perhaps in fiction, feature form."[63] The project received positive reviews from former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev,[64] The Guardian journalist Glenn Greenwald,[65] and reviewers from IndieWire,[66] San Francisco Chronicle,[67] and Newsday.[68] Hudson Institute adjunct fellow historian Ronald Radosh accused the series of historical revisionism,[69] while journalist Michael C. Moynihan accused the book of "moral equivalence" and said nothing within the book was "untold" previously.[70] Stone defended the program's accuracy to TV host Tavis Smiley by saying: "This has been fact checked by corporate fact checkers, by our own fact checkers, and fact checkers [hired] by Showtime. It's been thoroughly vetted ... these are facts, our interpretation may be different than orthodox, but it definitely holds up."[71] A review of Untold History at The Huffington Post by filmmaker Robert Orlando said there were "two flawed assumptions that underlie their master theory. First is the notion that the central conflict of the 20th century can be laid at the feet of a right-wing military conspiracy... Stone's second flawed assumption in Untold History is that capitalism coordinated the military-industrial complex's agenda."[72] Amidst other criticisms of Stone's documentary series and accompanying book The Untold History of the United States, Daily Beast contributor Michael C. Moynihan accused him of using untrustworthy sources, such as Victor Marchetti, whom Moynihan described as an antisemitic conspiracy theorist published in Holocaust denial journals. Moynihan wrote that: "There are hints at dark forces throughout the book: business interests controlled by the Bush family that were (supposedly) linked to Nazi Germany, a dissenting officer in the CIA found murdered after disagreeing with a cabal of powerful neoconservatives, suggestions that CIA director Allen Dulles was a Nazi sympathizer."[73]

Stone was interviewed in Boris Malagurski's documentary film The Weight of Chains 2 (2014), which deals with neoliberal reforms in the Balkans.[74]

On March 5, 2014, Stone and teleSUR premiered the documentary film Mi amigo Hugo (My Friend Hugo), a documentary about Venezuela's late president, Hugo Chávez, one year after his death. The film was described by Stone as a "spiritual answer" and tribute to Chávez.[75] At the end of 2014 according to a Facebook post Stone said he had been in Moscow to interview (former Ukrainian president) Viktor Yanukovych, for a "new English language documentary produced by Ukrainians".

Two years later in 2016, Stone was executive producer for Ukrainian-born director Igor Lopatonok's film Ukraine on Fire, interviewing pro-Russian figures surrounding the Revolution of Dignity such as Viktor Yanukovich and Vladimir Putin.[76] The film was regarded by critics as presenting a "Kremlin-friendly version" of the 2014 Maidan Revolution in Kyiv.[77] It was also criticized for advancing the Russian narrative about the revolution.[78][79]

Stone's series of interviews with Russian president Putin over the span of two years was released as The Putin Interviews, a four-night television event on Showtime on June 12, 2017.[80] On June 13, Stone and Professor Stephen F. Cohen joined John Batchelor in New York to record an hour of commentary on The Putin Interviews.[citation needed] In 2019, he released Revealing Ukraine, another film produced by Stone, directed by Lopatonok and featuring Stone interviewing Putin.[81] During these interviews, Putin made an unproven claim about Georgian snipers being responsible for the February 20 killings of protesters during the Euromaidan demonstrations, a hypothesis Stone himself had earlier supported on Twitter.[82]

In June 2021, Stone's documentary JFK Revisited: Through the Looking Glass was selected to be shown in the Cannes Premiere section at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival.[83]

In 2021, he also produced and featured in Qazaq: History of the Golden Man, directed by Lopatonok, an eight-hour film consisting of Stone interviewing Kazakh politician and former leader Nursultan Nazarbayev. The movie has been criticized for its non-confrontational approach in the interview and, because no opposition members were interviewed, according to some critics this resulted in a promotion of the authoritarian rule and cult of personality of Nazarbayev.[84][85] The film received at least $5 million funding from Nazarbayev's own charitable foundation, Elbasy, via the country's State Center for Support of National Cinema, according to the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. Stone and Lopatonok had denied any Kazakhstani government involvement.[84][86][87] According to Rolling Stone, "What little attention Qazaq did receive was largely negative, with critics decrying the film for its glowing depiction of Nazarbayev."[86]

In 2022, Stone directed and co-wrote Nuclear Now, a climate change documentary based on the book A Bright Future: How Some Countries Have Solved Climate Change and the Rest Can Follow written by the US scientists Joshua S. Goldstein and Staffan A. Qvist. The movie argues that nuclear energy is needed to fight climate change, as renewables alone will not be sufficient for the planet to obtain carbon neutrality before climate change becomes irreversible. Of the film, Stone stated, "People worry about nuclear waste and meanwhile the whole world is choking on fossil fuel waste. That’s silly. Trillions of dollars have been invested in solar and wind and hydropower. Everything possible is being discussed, except for nuclear... It has to be on the agenda."[88]

Other work

[edit]On September 15, 2008, Stone was named the artistic director of New York University's Tisch School of the Arts Asia in Singapore.[89]

Stone contributed a chapter to the 2012 book Last Word: My Indictment of the CIA in the Murder of JFK by Mark Lane and published by Skyhorse Publishing.[90] Skyhorse has published numerous other books with forewords or an introduction by Stone,[91] namely The JFK Assassination,[92] Reclaiming Parkland: Tom Hanks, Vincent Bugliosi, and the JFK Assassination in the New Hollywood,[93] The Plot to Overthrow Venezuela: How the US is orchestrating a coup for oil, Snowden:The Official Motion Picture Edition, The Putin Interviews and JFK: The CIA, Vietnam, and the Plot to Assassinate John F. Kennedy[94] which features a quote from Stone on the newest edition's cover: "Blows the lid right off our 'Official History.'"[95]

In 2022, he appeared in Theaters of War, discussing the role of the military in Hollywood.[96]

Directorial style

[edit]Many of Stone's films focus on controversial American political issues during the late 20th century, and as such were considered contentious at the times of their releases. They often combine different camera and film formats within a single scene, as demonstrated in JFK (1991), Natural Born Killers (1994) and Nixon (1995).[97] Roger Ebert called Stone "a filmmaker of feverish energy and limitless technical skills, able to assemble a bewildering array of facts and fancies and compose them into a film without getting bogged down."[98] Owen Gleiberman, who named Nixon the best film of 1995, called Stone, "the most exciting filmmaker of his time. You don’t just watch his movies—they get inside you, like drugs. [...] More than any director before him, he has captured the violent free-associative rhythms of a feral, jagged modern mind."[99][100] According to Quentin Tarantino, "[Stone] wants to make an impact. He wants to punch you in the face with this stuff and when you leave the theater, he wants you to leave with a big idea. [...] To me, Oliver Stone's films are very similar to the kind of films that Stanley Kramer used to make in the '50s and '60s, the big difference being that Stanley Kramer was kind of a clumsy filmmaker and Oliver Stone is cinematically brilliant."[101]

Influences

[edit]Stone listed Greek-French director Costa-Gavras as an early significant influence on his films. Stone mentioned that he "was certainly one of my earliest role models,...I was a film student at NYU when Z came out, which we studied. Costa actually came over with Yves Montand for a screening and was such a hero to us. He was in the tradition of Gillo Pontecorvo's The Battle of Algiers and was the man in that moment... it was a European moment."[102]

Personal life

[edit]Family

[edit]

Stone has been married three times, first to Najwa Sarkis Stone, a United Nations protocol attache, on May 22, 1971. They divorced in 1977. He then married Elizabeth Burkit Cox, an assistant in film production, on June 7, 1981.[103][104] They had two sons, Sean Stone/Ali (b. 1984) and Michael Jack (b. 1991). As a child, Sean acted in supporting roles in several of his father's films, and later worked for the Russia state media company RT America as a program host from 2015-2022.[105] Oliver and Elizabeth divorced in 1993. Stone has been married to Sun-jung Jung from South Korea since 1996, and the couple have a daughter, Tara (b. 1995).[106] Stone and Sun-jung live in Los Angeles.[107] Stone holds dual U.S. and French citizenship.[108]

Religion and humanism

[edit]Stone has been a practicing Buddhist since 1993.[109] Stone is also mentioned in Pulitzer Prize-winning American author Lawrence Wright's book Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the Prison of Belief as having been a member of Scientology for about a month, saying "It was like going to college and reading Dale Carnegie, something you do to find yourself."[110] In 1997, Stone was one of 34 celebrities to sign an open letter to then-German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, published as a newspaper advertisement in the International Herald Tribune, which protested against the treatment of Scientologists in Germany and compared it to the Nazis' oppression of Jews in the 1930s.[111] In 2003, Stone was a signatory of the third Humanist Manifesto.[112]

Legal issues

[edit]In 1999, Stone was arrested for driving under the influence of alcohol and possession of drugs, including fenfluramine, phentermine, meprobamate and a small amount of hashish. He pled guilty to two counts of driving while intoxicated and was ordered into a rehabilitation program.[113] He was arrested again on the night of May 27, 2005, in Los Angeles for possession of marijuana.[114][115][116] He was released the next day on a $15,000 bond.[115] In August 2005, Stone pleaded no contest and was fined $100.[117]

Sexual harassment allegations

[edit]In 2017, former Playboy model Carrie Stevens alleged that in 1991, Stone had "walked past me and grabbed my boob as he waltzed out the front door of a party."[118]

The allegation Stevens made surfaced after Stone announced he would no longer direct the Weinstein Company's television series Guantanamo following the revelation of the Harvey Weinstein sexual misconduct allegations.[118] Stone also drew criticism for his comments on Harvey Weinstein himself, saying:

I'm a believer that you wait until this thing gets to trial. I believe a man shouldn't be condemned by a vigilante system. It's not easy what he's going through, either. During that period he was a rival. I never did business with him and didn't really know him. I've heard horror stories on everyone in the business, so I'm not going to comment on gossip. I'll wait and see, which is the right thing to do.[119]

Later that day he withdrew his remarks, saying that he had been unaware of the extent of the allegations due to his travel schedule. "After looking at what has been reported in many publications over the last couple of days, I'm appalled and commend the courage of the women who've stepped forward to report sexual abuse or rape," he said.[119]

Melissa Gilbert accused Stone of "sexual harassment" during an audition for The Doors in 1991. Gilbert said that Stone told her to get on her hands and knees and say, "Do me baby." Gilbert reportedly refused and left the audition in tears, calling it humiliating. Stone released a statement denying the accusation. The film's casting director, Risa Bramon Garcia, contradicted her story as well, saying, "No actor was forced or expected to do anything that might have been uncomfortable, and most actors embraced the challenge".[120][121]

Political views

[edit]

Stone has been described as having left-wing political views.[122][123][124] Per FEC data, he has an extensive history of political donations, almost exclusively to Democratic candidates and PACs.[125] In a December 2024 podcast interview, Stone defined himself as an independent opposed to neoconservatism and a "real liberal" influenced by John Stuart Mill.[126] He has also drawn attention for his opinions on controversial world leaders such as Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, Hugo Chávez and Vladimir Putin.[127][128] In Showtime's The Putin Interviews, Stone called Joseph Stalin "the most famous villain in history, next to Adolf [Hitler]", who "left a horrible reputation, and stained the [Communist] ideology forever ... it's mixed with blood, and terror."[129] Stone has endorsed the works of author and United States foreign policy critic William Blum, saying that his books should be taught in schools and universities.[130]

U.S. presidential politics

[edit]Stone served as a delegate for Jerry Brown's campaign in the 1992 Democratic Party presidential primaries[131] and spoke at the 1992 Democratic National Convention.[132] In an interview with Bill Maher, Stone claimed that he met President Bill Clinton at the White House in 1995, but that Clinton kept the visit off the official agenda due to Stone's controversial reputation.[133]

Stone has suggested a link between 9/11 and the controversies of the 2000 election: "Does anybody make a connection between the 2000 election and the events of September 11th? ... Look for the thirteenth month!"[134] In 2024, Stone reflected that the day the U.S. Supreme Court ended the Florida recount in the 2000 presidential election was "the worst moment, for me, of this century," as he supported Al Gore and believes that George W. Bush was the worst president in U.S. history.[135]

According to Entertainment Weekly, Stone voted for Barack Obama as President of the United States in both the 2008 and 2012 elections.[136] Stone was quoted as saying at the time: "I voted for Obama because...I think he's an intelligent individual. I think he responds to difficulties well...very bright guy...far better choice, yes."[137] In 2012, Stone endorsed Ron Paul for the Republican nomination for president, citing his support for a non-interventionist foreign policy. He said that Paul is "the only one of anybody who's saying anything intelligent about the future of the world."[138] He later added: "I supported Ron Paul in the Republican primary...but his domestic policy...made no sense!"[137] In March 2016, Stone wrote on The Huffington Post indicating his support for Vermont U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders for the 2016 Democratic nomination.[139] In September 2016, Stone said he was voting for Green Party candidate Jill Stein for president.[140] He added that, as a progressive leftist, he felt forced to vote third party, as he believed neoconservatives like Hillary Clinton had taken over the Democratic Party. [141]

Speaking at the San Sebastián film festival, Stone said that many Americans had become disillusioned with Barack Obama's policies, having originally thought he would be "a man of great integrity." He said: "On the contrary, Obama has doubled down on the (George W.) Bush administration policies," and "has created...the most massive global security surveillance state that's ever been seen, way beyond East Germany's Stasi".[142]

In April 2018, Stone attended a press conference at the Fajr Film Festival in Tehran, where he likened Donald Trump to "Beelzebub", the biblical demonic figure.[143] Although Stone voted for Joe Biden in 2020, he criticized what he perceived to be the hypocrisy of the Democratic Party; Stone argued that the Democrats were not as concerned about Russian interference as they had been in 2016 when Trump won.[144] He reflected, "I sense the neoconservatives are jumping around Washington, getting their ammunition ready because they know this man, in the end, will come over to their bidding."[145] On his social media, Stone detailed eleven reasons why he could never vote for Trump, including his policies on Israel, Cuba and Venezuela, the assassination of Qasem Soleimani and his pardons of three court-martialed U.S. military officers who were accused or convicted of war crimes in Iraq and Afghanistan.[146] He additionally cited Trump's stances on climate change and immigration.[147]

On November 22, 2021, Stone penned an op-ed on The Hollywood Reporter, criticizing both Donald Trump and Joe Biden for not declassifying all records on the assassination of John F. Kennedy.[148] In July 2023, during an interview with Russell Brand, Stone stated that he regretted voting for Biden, because he feared that Biden could start World War III over the Russo-Ukrainian war.[149] Also in 2023, Stone donated to personal friend Robert F. Kennedy Jr.'s campaign for the 2024 Democratic presidential nomination.[150] In the 2024 general presidential election, Stone again voted for Kennedy who, after failing to secure the Democratic nomination, appeared on the ballot as the American Independent Party candidate.[151]

Holocaust controversy

[edit]

In a January 2010 press conference announcing his documentary series on the history of the United States, he said: "Hitler is an easy scapegoat throughout history and it's been used cheaply. He's the product of a series of actions. It's cause and effect." Just before commenting about Hitler, he mentioned Stalin: "We can't judge people as only 'bad' or 'good.'"[152] In response to Stone's comment about his intention to place Hitler "in context", Rabbi Marvin Hier of the Simon Wiesenthal Center said it "is like placing cancer in context, instead of recognizing cancer for what it really is—a horrible disease."[153]

Interviewed by The Sunday Times on July 25, 2010, Stone said: "Hitler did far more damage to the Russians than the Jewish people, 25 or 30 [million killed]." He objected to what he termed "the Jewish domination of the media", appearing to be critical of the coverage of the Holocaust, adding "There's a major lobby in the United States. They are hard workers. They stay on top of every comment, the most powerful lobby in Washington. Israel has fucked up United States foreign policy for years."[154][155] The remarks were criticized by Jewish groups, including the American Jewish Committee which compared his comments negatively to those of Mel Gibson.[156][157] Abraham Foxman of the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) said, "Oliver Stone has once again shown his conspiratorial colors with his comments about 'Jewish domination of the media' and control over U.S. foreign policy. His words conjure up some of the most stereotypical and conspiratorial notions of undue Jewish power and influence."[158]

Yuli Edelstein, the speaker of Israel's Knesset and the leading Soviet refusenik, described Stone's remarks as what "could be a sequel to The Protocols of the Elders of Zion",[159] as well as from Israel's Diaspora Affairs and Public Diplomacy Minister.[159]

A day later, Stone stated:

In trying to make a broader historical point about the range of atrocities the Germans committed against many people, I made a clumsy association about the Holocaust, for which I am sorry and I regret. Jews obviously do not control media or any other industry. The fact that the Holocaust is still a very important, vivid and current matter today is, in fact, a great credit to the very hard work of a broad coalition of people committed to the remembrance of this atrocity—and it was an atrocity.[160]

Two days later, Stone issued a second apology to the ADL, which was accepted. "I believe he now understands the issues and where he was wrong, and this puts an end to the matter," Foxman said.[161]

WikiLeaks

[edit]Oliver Stone is a vocal supporter of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. Stone signed a petition in support of Assange's bid for political asylum in June 2012.[162] In August 2012, he penned a New York Times op-ed with filmmaker Michael Moore on the importance of WikiLeaks and free speech.[163] Stone visited Assange in the Ecuadorian Embassy in April 2013 and commented, "I don't think most people in the US realize how important WikiLeaks is and why Julian's case needs support." He also criticized the documentary We Steal Secrets: The Story of WikiLeaks and the film The Fifth Estate, saying "Julian Assange did much for free speech and is now being victimised by the abusers of that concept".[164]

In June 2013, Stone and numerous other celebrities appeared in a video showing support for Chelsea Manning.[165][166]

Foreign policy

[edit]Stone called Saudi Arabia a major destabilizer in the Middle East. He also criticized the foreign policy of the United States, saying: "We made a mess out of Iraq, Syria, Libya, but it doesn't matter to the American public. It's okay to wreck the Middle East."[143]

Stone has had an interest in Latin America since the 1980s, when he directed Salvador, and later returned to make his documentary South of the Border about the left-leaning movements that had been taking hold in the region. He has expressed the view that these movements are a positive step toward political and economic autonomy for the region.[167] He supported Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez and admired the Colombian militant group FARC.[168]

Stone has criticized the U.S.-supported Operation Condor, a state terror operation that carried out assassinations and disappearances in support of South America's right-wing dictatorships in Argentina (see Dirty War), Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay.[169]

In December 2014, Stone made statements supporting the Russian government's narrative on Ukraine, portraying the 2014 Ukrainian Revolution of Dignity as a CIA plot. He also rejects the claim that former Ukrainian president (who was overthrown as a result of that revolution) Viktor Yanukovych was responsible for the killing of protesters as claimed by the succeeding Ukrainian government. Stone said Yanukovych was the legitimate president who was forced to leave Ukraine by "well-armed, neo-Nazi radicals". He said that in "the tragic aftermath of this coup, the West has maintained the dominant narrative of 'Russia in Crimea' whereas the true narrative is 'USA in Ukraine'".[170][171][172][173][174][175] James Kirchick of The Daily Beast criticized Stone's comments.[176][177] After the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Stone said that "Russia was wrong to invade."[178] However, he continued to blame the conflict on the U.S. and NATO, emphasizing his fear of a potential nuclear war and accusing the U.S. of seeking to dominate the world.[179][180]

In a June 2017 interview with The Nation to promote his documentary on Vladimir Putin, Stone rejected the narrative of the United States' intelligence agencies that Russia sought to influence the 2016 presidential election. Stone accused the CIA, FBI, and NSA of cooking the intelligence. He said: "The influence on the election from the Russians to me is absurd to the naked eye. Israel has far more influence on American elections through AIPAC. Saudi Arabia has influence through money... Sheldon Adelson and the Koch brothers have much more influence on American elections... And the prime minister of Israel comes to our country and addresses Congress to criticize the president's policy in Iran at the time—that's pretty outrageous."[181]

Russia passed a law in 2013 banning “gay propaganda” to minors, which has been criticized as being used for a crackdown on LGBTQ support.[182] In a 2019 interview with Putin, Stone said of the law that "It seems like maybe that's a sensible law." Stone later said he is not homophobic.[183][184]

Stone took the Russian Sputnik V vaccine for the COVID-19 virus while filming in Russia and the Pfizer vaccine upon his return to the return to the United States, calling himself "a pin cushion for American-Russian peace relations."[185][186]

Filmography

[edit]Feature films

[edit]| Year | Title | Director | Writer | Producer | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | Street Scenes 1970 | No | No | Associate | Documentary |

| 1973 | Sugar Cookies | No | No | Associate | |

| 1974 | Seizure | Yes | Yes | No | Also editor |

| 1978 | Midnight Express | No | Yes | No | |

| 1981 | The Hand | Yes | Yes | No | |

| 1982 | Conan the Barbarian | No | Yes | No | |

| 1983 | Scarface | No | Yes | No | |

| 1985 | Year of the Dragon | No | Yes | No | |

| 1986 | Salvador | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 8 Million Ways to Die | No | Yes | No | ||

| Platoon | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| 1987 | Wall Street | Yes | Yes | No | |

| 1988 | Talk Radio | Yes | Yes | No | |

| 1989 | Born on the Fourth of July | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 1990 | Blue Steel | No | No | Yes | |

| Reversal of Fortune | No | No | Yes | ||

| 1991 | The Doors | Yes | Yes | No | Also soundtrack album director |

| Iron Maze | No | No | Executive | ||

| JFK | Yes | Yes | Yes | Also soundtrack album director | |

| 1992 | South Central | No | No | Executive | |

| Zebrahead | No | No | Executive | ||

| 1993 | The Joy Luck Club | No | No | Executive | |

| Heaven & Earth | Yes | Yes | Yes | Also soundtrack album director | |

| 1994 | Natural Born Killers | Yes | Yes | Executive | |

| The New Age | No | No | Executive | ||

| 1995 | Killer: A Journal of Murder | No | No | Executive | |

| Gravesend | No | No | No | Presenter | |

| Nixon | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| 1996 | Freeway | No | No | Executive | |

| The People vs. Larry Flynt | No | No | Executive | ||

| Evita | No | Yes | No | ||

| 1997 | U Turn | Yes | Uncredited | No | |

| Cold Around the Heart | No | No | Executive | ||

| 1998 | The Last Days of Kennedy and King | No | No | Executive | Documentary |

| Savior | No | No | Yes | ||

| 1999 | The Corruptor | No | No | Executive | |

| Any Given Sunday | Yes | Yes | Executive | ||

| 2003 | Comandante | Yes | Yes | Yes | Documentary, also narrator |

| 2004 | Alexander | Yes | Yes | No | |

| 2006 | World Trade Center | Yes | No | No | |

| 2008 | W. | Yes | No | No | |

| 2009 | South of the Border | Yes | No | No | Documentary |

| 2010 | Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps | Yes | No | Uncredited | |

| 2012 | Castro in Winter | Yes | No | No | Documentary |

| Savages | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| 2014 | Mi amigo Hugo | Yes | No | No | Documentary |

| 2015 | A Good American | No | No | Executive | |

| 2016 | Ukraine on Fire | No | No | Executive | |

| Snowden | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| All Governments Lie | No | No | Executive | Documentary | |

| 2019 | Revealing Ukraine | No | No | Executive | |

| 2021 | JFK Revisited: Through the Looking Glass | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Qazaq: History of the Golden Man | No | No | Executive | ||

| 2022 | Nuclear Now | Yes | Yes | No | |

| 2024 | Lula | Yes | Yes | — |

Television

[edit]| Year | Title | Director | Writer | Producer | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | Wild Palms | No | No | Executive | TV Mini-Series |

| 1995 | Indictment: The McMartin Trial | No | No | Executive | TV movie |

| 2001 | The Day Reagan Was Shot | No | No | Executive | |

| 2003–2004 | America Undercover | Yes | Yes | No | Episodes Looking for Fidel and Persona Non Grata |

| 2012–2013 | The Untold History of the United States | Yes | Yes | Executive | TV series documentary |

| 2017 | The Putin Interviews | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 2021 | JFK: Destiny Betrayed | Yes | No | No |

Awards and honors

[edit]| Year | Title | Academy Awards | BAFTA Awards | Golden Globe Awards | Golden Raspberry Awards | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominations | Wins | Nominations | Wins | Nominations | Wins | Nominations | Wins | ||

| 1986 | Salvador | 2 | |||||||

| Platoon | 8 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | |||

| 1987 | Wall Street | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1989 | Born on the Fourth of July | 8 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 4 | |||

| 1991 | JFK | 8 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | ||

| 1993 | Heaven & Earth | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 1994 | Natural Born Killers | 1 | |||||||

| 1995 | Nixon | 4 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 1997 | U Turn | 2 | |||||||

| 2004 | Alexander | 6 | |||||||

| 2010 | Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps | 1 | |||||||

| 2016 | Snowden | 1 | |||||||

| Total | 31 | 9 | 10 | 4 | 18 | 10 | 10 | 1 | |

Directed Academy Award Performances

| Year | Performer | Film | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Award for Best Actor | |||

| 1987 | James Woods | Salvador | Nominated |

| 1988 | Michael Douglas | Wall Street | Won |

| 1990 | Tom Cruise | Born on the Fourth of July | Nominated |

| 1996 | Anthony Hopkins | Nixon | Nominated |

| Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor | |||

| 1987 | Tom Berenger | Platoon | Nominated |

| Willem Dafoe | Nominated | ||

| 1992 | Tommy Lee Jones | JFK | Nominated |

| Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress | |||

| 1996 | Joan Allen | Nixon | Nominated |

Honors

Commander of the Order of Intellectual Merit (Morocco, 2003)[187]

Commander of the Order of Intellectual Merit (Morocco, 2003)[187]- 2007: Lifetime Achievement Award of Zurich Film Festival

- 2024: made Commander of France’s Order of Arts and Letters

Bibliography

[edit]Books

[edit]- Oliver Stone's Platoon & Salvador. Co-authored with Richard Boyle. New York: Vintage Books, 1987. ISBN 978-0394756295. 254 pages.

- JFK: The Book of the Film: The Documented Screenplay. Co-authored with Zachary Sklar. Hal Leonard Corporation, 1992. ISBN 978-1557831279.

- A Child's Night Dream: A Novel. New York: Macmillan, 1998. ISBN 978-0312194468.

- Oliver Stone: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi, 2001. ISBN 978-1578063031.

- Last Word: My Indictment of the CIA in the Murder of JFK. Co-authored with Mark Lane & Robert K. Tanenbaum. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2012. ISBN 978-1620870709.

- The Untold History of the United States. Co-authored by Peter Kuznick. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012. ISBN 978-1451613513.

- The Putin Interviews. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2017. ISBN 978-1510733435.

- Chasing the Light: Writing, Directing, and Surviving Platoon, Midnight Express, Scarface, Salvador, and the Movie Game (July 2020)[188]

Interviews

[edit]- Crowdus, Gary. "Clarifying the Conspiracy: An Interview with Oliver Stone". Cinéaste, Vol. 19, No. 1, 1992. pp. 25–27. JSTOR 41688064.

- Long, Camilla. "Oliver Stone: Lobbing Grenades in All Directions". Archived from the original. The Sunday Times, July 25, 2010.

- Louis Theroux, January 4, 2021, BBC Radio 4 'Grounded' (Omits mention of: Stone's support for whistleblower Julian Assange; "JFK"; "The Untold History of the United States") https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/p091pfzv.

Screenplays

[edit]- Snowden: Official Motion Picture Edition. Co-authored with Kieran Fitzgerald. Skyhorse Publishing, 2016. ISBN 978-1510719712.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Oliver Stone Experience". The Official Oliver Stone website. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- ^ "The 10 Best Oliver Stone Films". Rolling Stone. June 18, 2012. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- ^ "Oliver Stone: 10 essential films". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on December 20, 2017. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- ^ "Oliver Stone and Vladimir Putin's Unlikely Friendship, and the Controversy Behind It". December 21, 2022.

- ^ "Oliver Stone Draws Fire for 'Revolt' Theory". ABC News. January 6, 2006. Archived from the original on May 15, 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

Conspiracy theorist/filmmaker Oliver Stone believes that the mediocrity of Hollywood movies, ...

- ^ "Oliver Stone finds in 'Snowden' a real government conspiracy". The Seattle Times. September 13, 2016. Archived from the original on December 17, 2018. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

Stone being the conspiracy theorist filmmaker of our time ...

- ^ "In 'Snowden', Oliver Stone depicts the NSA leaker as pure hero". Chicago Sun-Times. September 14, 2016. Archived from the original on December 17, 2018. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

master filmmaker/agitator/conspiracy theorist/rebel Oliver Stone ...

- ^ Purdum, Todd (September 18, 2008). "If You Liked 'Nixon'..." The Hive. Archived from the original on August 15, 2020. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

the American cinema's reigning conspiracy theorist, Stone ...

- ^ "Oliver Stone tells Stephen Colbert that Vladimir Putin has been 'insulted' and 'abused'". Newsweek. June 13, 2017. Archived from the original on December 17, 2018. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

... professional conspiracy theorist Oliver Stone

- ^ Greg Hengler (January 4, 2013). "Director Oliver Stone Tells Us Why America Is Not Exceptional". Archived from the original on October 29, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "washingtonpost.com: OLIVER STONE'S MOTHER LODE". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- ^ a b "Biography: Oliver Stone on Filmmaking, Platoon, Vietnam, Nicaragua & El Salvador (1987)". YouTube. National Press Club. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ Riordan, James (1996). Stone: The Controversies, Excesses and Exploits of a Radical Filmmaker. Hyperion. p. 6. ISBN 978-0786860265.

- ^ "Télématin" (France 2), September 28, 2010.

- ^ "The religion of director Oliver Stone". Adherents.com. Archived from the original on December 2, 2010. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

- ^ "Oliver Stone's Mother Lode". The Washington Post. September 11, 1997. Archived from the original on March 27, 2012. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ Timothy Rhys (April 15, 1995). "Oliver Stone Unturned: The Natural Born Killers Director on War, Art, and Religion". MovieMaker. Archived from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ Cadwalladr, Carole (July 18, 2010). "Oliver Stone and the politics of film-making". The Observer. paragraphs 31 and 42. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017. Retrieved July 22, 2010.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Galloway, Stephen. Oliver Stone: Less Crazy After All These Years. The Hollywood Reporter June 13, 2012. [1] Archived August 10, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Accessed September 28, 2017

- ^ ANTHES, EMILY (September 19, 2003). "Famous Failures". Yale Daily News. Archived from the original on October 22, 2011. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

- ^ Lin, Ho (September 16, 1967). "Famous Veterans: Oliver Stone". Military.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ Kreisler, Harry. "Conversations with history – a discussion with Oliver Stone (23 May 2016)". www.uctv.tv. UC TV, University of California, Berkeley. Archived from the original on November 13, 2018. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- ^ Famous Failures. Yale Daily News September 19, 2003. [2] Archived September 28, 2017, at the Wayback Machine accessed September 28, 2017

- ^ Stone, Oliver (2020). Chasing the Light. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 43. ISBN 9780358522508.

- ^ Riordan, James (1996). Stone: The Controversies, Excesses, and Exploits of a Radical Filmmaker. Hyperion Books. p. 55. ISBN 978-0786860265.

- ^ Zoller Seitz, Matt (2016). The Oliver Stone Experience. Abrams. p. 49. ISBN 9781419717901.

- ^ a b "NARA Release". Imgur. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ C à vous - France Télévisions (October 8, 2020). Oliver Stone : invité exceptionnel ! - C à Vous - 07/10/2020. Retrieved December 23, 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 - Grounded with Louis Theroux - Oliver Stone: Nine things we learned when he spoke to Louis Theroux". BBC. Retrieved December 21, 2024.

- ^ Stone, Oliver (2020). Chasing the Light. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 67. ISBN 9780358346234.

- ^ U-M Stamps School of Art & Design (November 26, 2012). Oliver Stone: Untold - An Interview with Bob Woodruff. Retrieved January 12, 2025 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Harvard College Calendar". Harvard College Calendar. Retrieved December 28, 2024.

- ^ "Oliver Stone: on being 19 in war, and for a county addicted to it | Responsible Statecraft". responsiblestatecraft.org. Retrieved December 28, 2024.

- ^ "IMAGO". www.imago-images.com. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ Seitz, Matt (October 28, 2013). "Oliver Stone on New York in the Sixties and Seventies and Taking Film Classes With Martin Scorsese". Vulture. New York Magazine. Archived from the original on October 31, 2013. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- ^ M.J. Simpson Interview with Lloyd Kaufman Archived June 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Flinn, John (January 10, 2004). "The real Billy Hayes regrets 'Midnight Express' cast all Turks in a bad light". Seattlepi.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ Krassner, Paul (January 6, 2005). "Oliver Stone Apologizes to Turkey". Laweekly.com. Archived from the original on July 26, 2012. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ "The Total Film Interview – Oliver Stone". Total Film. November 1, 2003. Archived from the original on January 4, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2008.

- ^ "Channel 4's 100 Greatest War Movies of All Time". Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ^ Chow, Andrew R. (December 11, 2019). "See the 25 New Additions to the National Film Registry, From Purple Rain to Clerks". Time. New York, NY. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- ^ "She Slams 'Doors' on Portrayal". New York Post. March 1991.

- ^ Clash, Jim (January 25, 2015). "Doors Drummer John Densmore On Oliver Stone, Cream's Ginger Baker (Part 3)". Forbes. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ "Bill Summary & Status – 102nd Congress (1991–1992) – S.J.RES.282 – CRS Summary – THOMAS (Library of Congress)". Thomas.loc.gov. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ^ "Final Report of the Assassination Records Review Board". Fas.org. May 30, 2008. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

- ^ Petersen, Scott. "Oliver Stone: Natural Born Director". Craveonline.com. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

- ^ ""Natural Born Killers", shooting draft, revised by Richard Rutowski & Oliver Stone". www.dailyscript.com. Archived from the original on August 6, 2019. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- ^ "Venice Film Festival (1994)". IMDb. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- ^ Alexander – Words from Oliver Stone: Thank you very much... Archived October 12, 2013, at archive.today. Facebook. Retrieved on May 22, 2014.

- ^ "Money Never Sleeps". IMDb. Archived from the original on September 15, 2009. Retrieved September 7, 2009.

- ^ Kate Stanhope (May 22, 2017). "Weinstein TV Nabs Oliver Stones Guantanamo Prison Drama". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 22, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^

"Oliver Stone to direct Guantánamo Bay TV series". Miami Herald. May 22, 2017. Archived from the original on May 24, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

Stone plans to direct the entire first season of the show, which was created by Daniel Voll.

- ^ Denise Petski (May 22, 2017). "Weinstein TV Acquires Guantanamo Series From Oliver Stone & Daniel Voll". Deadline. Archived from the original on May 22, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ Joe Otterson (May 22, 2017). "Weinstein Company Acquires Oliver Stone TV Series Guantanamo". Variety magazine. Archived from the original on May 24, 2017.

- ^ "Oliver Stone Clarifies Comments, Backs Out of 'Guantanamo' TV Series If Weinstein Co. Involved". The Hollywood Reporter. October 12, 2017. Archived from the original on April 16, 2020. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ Svetkey, Benjamin (July 20, 2020). "Oliver Stone's Reel History". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 18, 2020. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- ^ Armstrong, Deborah L. (March 13, 2024). "George Soros' "Reporters" Write Hit Piece Smearing Oliver Stone's Co-Producer". Medium. Retrieved December 21, 2024.

- ^ Richard Corliss (September 27, 2007). "South of the Border: Chávez and Stone's Love Story". Time. Archived from the original on May 21, 2013. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ^ Stone: Film an intro to Chávez and his movement Archived June 1, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, by Ian James, Associated Press, May 29, 2010

- ^ Oliver Stone (June 28, 2010). "Oliver Stone Responds to New York Times Attack". Truthdig. Archived from the original on July 3, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ^ Lowry, Brian (November 11, 2012). "Review: 'Oliver Stone's Untold History of the United States'". Variety. Archived from the original on December 15, 2012. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ^ "Digital Catalog – The Untold History of the United States". Catalog.simonandschuster.com. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ^ Ed Rampell "Q&A: Oliver Stone on Israel, Palestine and Newt Gingrich", "The Jewish Daily Forward", January 15, 2012

- ^ Gorbachev on Untold History, October 2012. Books.simonandschuster.com. October 15, 2013. ISBN 9781451616446. Archived from the original on September 22, 2014. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ Glenn Greenwald "Various Items: Oliver Stone is releasing a new book" Archived March 17, 2017, at the Wayback Machine The Guardian. October 30, 2012

- ^ "Oliver Stone Premieres His Daring New Showtime Series 'Untold History of the United States' in New York." Archived January 9, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, Indiewire, October 8, 2012

- ^ David Wiegand (November 8, 2012). "'The Untold History' review: Oliver Stone". SFGate. Archived from the original on December 1, 2012. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ^ "'Oliver Stone's Untold History' review". Newsday.com. November 11, 2012. Archived from the original on November 7, 2013. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ^ Ronald Radosh (November 12, 2012). "A Story Told Before: Oliver Stone's recycled leftist history of the United States". The Weekly Standard. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- ^ Michael C. Moynihan (November 19, 2012). "Oliver Stone's Junk History of the United States Debunked". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on December 4, 2012. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- ^ "Video: Oliver Stone & Peter Kuznick, Part 1 | Watch Tavis Smiley Online | PBS Video". Video.pbs.org. September 13, 2011. Archived from the original on January 7, 2013. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ^ Orlando, Robert (September 17, 2014). "Untold (or Retold?) History : Oliver Stone's Showtime Series". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on July 10, 2017. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ Moynihan, Michael (November 19, 2012). "Oliver Stone's Junk History of the United States Debunked". Archived from the original on January 9, 2022. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ "Politika.rs". Politika.rs. January 28, 2015. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ ""Mi Amigo Hugo" Trailer". You Tube. February 28, 2014. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ^ Sanders, Lewis (November 22, 2016). "Putin's celebrity circle". dw.com. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- ^ Kozlov, Vladimir (November 23, 2016). "Oliver Stone-Produced Ukraine Doc Causes Stir in Russia, TV Network Ramps up Security Amid Threats". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- ^ (Vlast.kz), Vyacheslav Abramov; (OCCRP), Ilya Lozovsky (October 10, 2022). "Oliver Stone Documentary About Kazakhstan's Former Leader Nazarbayev Was Funded by a Nazarbayev Foundation". OCCRP. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- ^ Karatnycky, Adrian (October 16, 2024). "The Stubborn Legend of a Western 'Coup' in Ukraine". Foreign Policy. Retrieved October 14, 2024.

- ^ "Oliver Stone's Four-Hour Interview With Vladimir Putin to Premiere on Showtime". Archived from the original on May 1, 2017. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (July 26, 2019). "Oliver Stone Says He's Not Homophobic After Calling Russia's Anti-Gay Law 'Sensible'". Yahoo Entertainment. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- ^ Echols, William; Yarst, Nik (July 15, 2019). "Vladimir Putin Speaks with Oliver Stone: New Interview – Old False Claims". Polygraph.info. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ "Cannes Film Festival 2021 Lineup: Sean Baker, Wes Anderson, and More Compete for Palme d'Or". IndieWire. Archived from the original on July 7, 2021. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ a b "Oliver Stone derided for film about 'modest' former Kazakh president". The Guardian. July 11, 2021. Archived from the original on August 4, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Aushakimova, Assel. "Oliver Stone's lavish Nazarbayev documentary is just the latest blow to independent Kazakhstani filmmakers". The Calvert Journal. Archived from the original on August 18, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Blistein, Jon (October 12, 2022). "You'll Never Guess Where Oliver Stone Allegedly Got $5 Million to Make His Glowing Doc About Kazakhstan's Ex-Authoritarian Ruler". Rolling Stone. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- ^ (Vlast.kz), Vyacheslav Abramov; (OCCRP), Ilya Lozovsky (October 10, 2022). "Oliver Stone Documentary About Kazakhstan's Former Leader Nazarbayev Was Funded by a Nazarbayev Foundation". OCCRP. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- ^ Dinneen, Steve (June 22, 2023). "Oliver Stone on Putin, nuclear power and feeling like an outsider". CityAM. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "Oliver Stone Named Artistic Director". tischasia.nyu.edu.sg. Archived from the original on August 17, 2015. Retrieved June 5, 2015.

- ^ Lane, Mark (November 2012). Last Word: My Indictment of the CIA in the Murder of JFK. Skyhorse. ISBN 9781620870709.

- ^ "Search Results". Skyhorse Publishing. Archived from the original on February 18, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- ^ DiEugenio, James (May 1, 2018). The JFK Assassination. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781510739840. Archived from the original on January 9, 2022. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- ^ DiEugenio, James (September 20, 2016). Reclaiming Parkland: Tom Hanks, Vincent Bugliosi, and the JFK Assassination in the New Hollywood. Skyhorse. ISBN 9781510707771.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Prouty, L. Fletcher (April 2011). JFK: The CIA, Vietnam, and the Plot to Assassinate John F. Kennedy. Skyhorse Publishing Inc. ISBN 9781616082918. Archived from the original on January 9, 2022. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- ^ "JFK". Skyhorse Publishing. Archived from the original on February 18, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- ^ "Top Gun for hire: Why Hollywood is the US military's best wingman". TheGuardian.com. May 26, 2022.

- ^ James Riordan (September 1996). Stone: A Biography of Oliver Stone. New York: Aurum Press. p. 377. ISBN 1-85410-444-6.

- ^ "JFK movie review & film summary (1991) | Roger Ebert". www.rogerebert.com. Retrieved January 12, 2025.

- ^ "Nixon". EW.com. Retrieved January 15, 2025.

- ^ "1995 The Best & Worst/Movies". EW.com. Retrieved January 15, 2025.

- ^ Tarantino, Quentin; Peary, Gerald (1998). Quentin Tarantino: interviews. Conversations with filmmakers series. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-050-4.

- ^ Major, Wade (Fall 2009). "World Class". DGA. Directors Guild of America. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ Stone, Oliver (2001). Oliver Stone: Interviews — Oliver Stone, Charles L. P. Silet — Google Books. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781578063031. Archived from the original on November 15, 2021. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ^ O'Donnell, Monica M. (1984). Contemporary Theatre, Film and Television – Monica M. O'Donnell – Google Books. ISBN 9780810320642. Archived from the original on January 9, 2022. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ^ Gray, Rosie (March 9, 2015). "Jesse Ventura's Son And Oliver Stone's Son Get A Show At Russia Today". BuzzFeed News. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- ^ "63rd Annual Cannes Film Festival – 'Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps' Premiere". Life May 14, 2010 Archived June 10, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (Winter 2017). "In His Words: Director Oliver Stone", Stand, American Civil Liberties Union p. 31.

- ^ "Oliver Stone on 'The Putin Interview': The Russian President 'Is a Smart, Soft Man'". Observer. June 12, 2017. Retrieved December 24, 2024.

- ^ "Oliver Stone Unturned: The Natural Born Killers Director on War, Art, and Religion - MovieMaker Magazine". www.moviemaker.com. April 15, 1995. Retrieved December 20, 2024.

- ^ "Nine Celebrity Morsels from Lawrence's Wright's Scientology Book". Theatlanticwire.com. January 17, 2013. Archived from the original on September 19, 2013. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ Drozdiak, William (January 14, 1997). U.S. Celebrities Defend Scientology in Germany Archived July 24, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post, p. A11

- ^ "Notable Signers". Humanism and Its Aspirations. American Humanist Association. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012. Retrieved October 6, 2012.

- ^ Reed, Christopher (August 26, 1999). "Oliver Stone ready for rehab". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 1, 2025.

- ^ "Director Oliver Stone arrested". CNN News. May 28, 2005. Archived from the original on October 10, 2008. Retrieved October 15, 2008.

- ^ a b "Director Oliver Stone arrested". CNN. May 28, 2005. Archived from the original on August 13, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ "Oliver Stone ends pot case - UPI.com". UPI. Retrieved January 1, 2025.

- ^ "Oliver Stone enters plea in pot charge". USA Today. August 11, 2005. Archived from the original on January 9, 2022. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

- ^ a b Maane Khatchatourian, Oliver Stone Accused of Groping Former Playboy Model in '90s Archived December 12, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Variety (October 13, 2017).

- ^ a b Brzeski, Patrick (October 12, 2017). "Oliver Stone on Harvey Weinstein: 'It's Not Easy What He's Going Through'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 16, 2020.

- ^ Loughrey, Clarisse (November 21, 2017). "Oliver Stone accused of sexual harassment by Melissa Gilbert". The Independent. Archived from the original on December 2, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2021.

- ^ Cooney, Samantha (March 27, 2019). "Here Are All the Public Figures Who've Been Accused of Sexual Misconduct After Harvey Weinstein". Time. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ^ Tayler, Jeffrey (May 13, 2014). "Oliver Stone's Disgraceful Tribute to Hugo Chávez". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- ^ "Oliver Stone gets award at Croatian leftist film festival". Khaleej Times. Agence France-Presse. April 4, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2024.

- ^ "Oliver Stone's son in Iran to "prepare" documentary". Reuters. September 6, 2011. Archived from the original on March 25, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- ^ "Donor Lookup". OpenSecrets. Retrieved December 28, 2024.

- ^ Russia vs Ukraine, JFK Assassination, Trump vs Deep State w/ Oliver & Sean Stone | PBD Podcast | 522. Retrieved December 20, 2024 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ Nazaryan, Alexander (June 8, 2017). "Oliver Stone defends Vladimir Putin against Megyn Kelly". Newsweek. Archived from the original on June 8, 2017. Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- ^ Wilson, Greg. "Oliver Stone: Hitler and Stalin Weren't So Bad". NBC Chicago. Archived from the original on June 15, 2017. Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- ^ The Putin Interviews, Episode 4.

- ^ "Oliver Stone Remembers Anti-Imperialist Journalist William Blum, Chronicler of CIA Crimes". December 14, 2018. Archived from the original on November 29, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ Maureen Dowd; Frank Rich (July 14, 1992). "DEMOCRATS IN NEW YORK – GARDEN DIARY; Brown in Gotham City: The 'Penguin' Returns". The New York Times. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ^ "The 90's raw: Eddie Tape #111 – Democratic convention". Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ^ Club Random Podcast (November 19, 2023). Oliver Stone | Club Random with Bill Maher. Retrieved January 12, 2025 – via YouTube.

- ^ Friend, Tad (October 15, 2001). "Oliver Stone's Chaos Theory". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Archived from the original on February 16, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ Russia vs Ukraine, JFK Assassination, Trump vs Deep State w/ Oliver & Sean Stone | PBD Podcast | 522. Retrieved December 19, 2024 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ Schou, Solvej. "Oliver Stone on Obama: 'I hope he wins'". Entertainment Weekly Inc. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ a b "Oliver Stone on Voting For Obama". Archived from the original on November 1, 2012. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ "Director Oliver Stone on History. And America, Jim Morrison & Ron Paul". Rock Cellar Magazine. January 2012. Archived from the original on January 29, 2012. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ^ Oliver Stone. "Why I'm For Bernie Sanders". Huffington Post.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2016. Retrieved May 29, 2016.

- ^ Michael Hainey (September 12, 2016). "Oliver Stone Talks Secrets, Spies, and Snowden". Wired.com. Archived from the original on September 13, 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- ^ USA News Online (June 19, 2017). 'Trump Was Slapped in the Face' Tucker Chats With Oliver Stone About 'The Puti. Retrieved December 21, 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Obama-era surveillance worse than Stasi, says Oliver Stone Archived August 12, 2017, at the Wayback Machine". Yahoo News. September 22, 2016.

- ^ a b "Oliver Stone Compares Trump to "Beelzebub" at Iranian Film Festival Archived July 1, 2018, at the Wayback Machine". The Hollywood Reporter. April 25, 2018.

- ^ Stone, Oliver [@TheOliverStone] (November 13, 2020). "(1/3) Although I voted for @JoeBiden, I can't help but note that the #Democrats haven't cried foul over this weird election counting that we're going through. What happened – no #Russian interference this time? https://t.co/mIDHpA6ZrF" (Tweet). Archived from the original on March 14, 2022. Retrieved December 2, 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ Stone, Oliver [@TheOliverStone] (November 13, 2020). "(3/3) It would be a disaster for @JoeBiden to seek out another hotspot right away – Syria? – but who really knows? I sense the #neocons are jumping around #Washington, getting their ammunition ready because they know this man, in the end, will come over to their bidding" (Tweet). Archived from the original on March 14, 2022. Retrieved December 2, 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ Stone, Oliver [@TheOliverStone] (January 15, 2021). "#Trump's dangerous foreign legacy" (Tweet). Retrieved January 10, 2025 – via Twitter.

- ^ Stone, Oliver [@TheOliverStone] (October 22, 2020). "Dropped off my ballot yesterday. Couldn't #vote Third Party this time. @realDonaldTrump has had 4 years, and all I see is more chaos and uncertainty. There are 3 fundamental reasons I can't vote for him" (Tweet). Retrieved January 10, 2025 – via Twitter.

- ^ Stone, Oliver (November 22, 2021). "Guest Column: Oliver Stone Calls Out President for Not Yet Declassifying All JFK Assassination Records". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ^ Hall, Alexander (July 29, 2023). "Director Oliver Stone Declares He 'Made a Mistake' When He Voted for Biden, Says He May Start 'World War 3'". Fox News. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- ^ "RFK Jr. Raised $8.7 Million With Hollywood, Republican Donors for 202…". archive.is. October 14, 2023. Retrieved December 20, 2024.

- ^ Tucker Carlson (January 10, 2025). Oliver Stone & Peter Kuznick: War Profiteering, Nuclear Tech, NATO v. Russia, & War With Iran. Retrieved January 11, 2025 – via YouTube.

- ^ Hibberd, James (January 11, 2010). "Oliver Stone says Hitler an 'easy scapegoat'". Reuters. The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ^ "Wiesenthal Center Blasts Oliver Stone's 'Hitler Was A Scapegoat' Remarks". Simon Wiesenthal Center. January 15, 2010. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ^ Long, Camilla (July 25, 2010). "Oliver Stone: Lobbing grenades in all directions". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on September 14, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2020.(subscription required)

- ^ "Oliver Stone: Jewish Control of the Media Is Preventing Free Holocaust Debate". Haaretz. Archived from the original on May 4, 2020. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ^ Barnes, Brooks (July 26, 2010). "Oliver Stone Controversy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 12, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ^ "AJC: 'Oliver Stone has Outed Himself as an Anti-Semite'". American Jewish Committee. July 26, 2010. Archived from the original on July 29, 2010.

- ^ Szalai, Georg (July 26, 2010). "Oliver Stone Slammed for Anti-Semitism". The Hollywood Reporter. Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 14, 2019.

- ^ a b Hoffman, Gil Stern. "Israel Slams Oliver Stone's Interview". Archived from the original Archived July 29, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. The Jerusalem Post, July 26, 2010.

- ^ "Oliver Stone 'Sorry' About Holocaust Comments" Archived November 26, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. The Wall Street Journal, July 26, 2010.

- ^ Szalai, Georg. "Oliver Stone, ADL Settle Their Differences". Archived August 31, 2010, at the Wayback Machine The Hollywood Reporter, October 14, 2010.

- ^ "Moore, Glover, Stone, Maher, Greenwald, Wolf, Ellsberg Urge Correa to Grant Asylum to Assange". Just Foreign Policy. June 22, 2012. Archived from the original on April 7, 2013. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ^ "WikiLeaks and Free Speech". The New York Times. August 20, 2012. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ^ Child, Ben (April 11, 2013). "Oliver Stone meets Julian Assange and criticises new WikiLeaks films". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on December 28, 2016. Retrieved December 12, 2016.

- ^ Celeb video: 'I am Bradley Manning' – Patrick Gavin Archived January 10, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Politico.Com (June 20, 2013). Retrieved on May 22, 2014.

- ^ I am Bradley Manning (full HD). I am Bradley Manning. June 19, 2013. Archived from the original on November 24, 2022. Retrieved December 2, 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ Ann Hornaday (June 23, 2010). "Director Stone leaves no passion unstoked, and Silverdocs film is no exception". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 10, 2015. Retrieved October 10, 2013.