Mario Paint

| Mario Paint | |

|---|---|

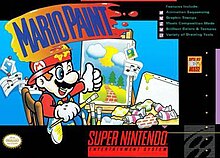

North American box art | |

| Developer(s) | |

| Publisher(s) | Nintendo |

| Director(s) | Hirofumi Matsuoka |

| Producer(s) | Gunpei Yokoi |

| Programmer(s) |

|

| Artist(s) | Hirofumi Matsuoka |

| Composer(s) |

|

| Series | Mario |

| Platform(s) | Super Nintendo Entertainment System |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Art tool |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Mario Paint[a] is a 1992 art creation video game developed by Nintendo Research & Development 1 (R&D1) and Intelligent Systems and published by Nintendo for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System.[1][2] Mario Paint consists of a raster graphics editor, an animation program, a music composer, and a point and click minigame, all of which are designed to be used with the Super NES Mouse peripheral, which the game was packaged and sold with. Per its name, the game is Mario-themed, and features sprites and sound effects that are taken from or in the vein of Super Mario World.

Mario Paint sold very well following its release and is one of the best-selling SNES games, with over 2.3 million copies sold. The game was released to fairly positive contemporaneous reviews; critics highlighted its accessibility, features, innovative design, and educational potential, but criticized unnecessary limitations on creation that rendered it unviable for serious creation. Retrospective reviews have been more positive, praising the game as "memorable", "addictive", "unique", and "ingenious", and it has been deemed one of the best SNES games of all time. Mario Paint's music composer in particular has been used to create original songs, covers, and remixes using the game's sounds and limitations.

A 1998 successor game, Mario no Photopi for the Nintendo 64, was never released outside of Japan. This was followed by a series, Mario Artist, released for the 64DD peripheral starting in 1999; however, only four titles were released in Japan only before the rest were canceled by 2000. Similar titles and game creation systems released by Nintendo since, such as WarioWare D.I.Y., Super Mario Maker, and Super Mario Maker 2, include features from and references to Mario Paint; Super Mario Maker in particular was originally envisioned as a Mario Paint title for the Wii U.

Gameplay

[edit]

According to the manual, two parts of Mario Paint are meant to familiarize the user with the SNES Mouse: the title screen, where users can click on each letter in the logo and each element on the screen to prompt a respective Easter egg;[3] and a fly-swatting minigame, "Gnat Attack", where the player must swat 100 insects before fighting a boss named King Watinga.[4] The minigame has three levels, and after they are completed, the game starts over with the enemies swarming in and attacking at faster speed.[5] Content creation features of the program include a drawing board, a coloring book, an animation tool (called "Animation Land"), and a music composer. Collages can be saved at a time in the program to be loaded at later usage of the software[6] or recorded to VCR.[4] In the coloring book, the user can color-in and edit four pre-made black-and-white drawings, including one featuring Yoshi and Mario, another featuring various animals, a greeting card, and an underwater scene.[7]

The drawing board is where original paintings can be created. A user can choose from 15 colors and 75 patterns.[3] After choosing, the user can draw with a pen (small, medium, or large) and airbrush; [8] fill in a closed area the selected texture with the "paint brush" tool;[9] and create perfectly straight lines, rectangles, and circles that is the color or pattern selected (either fully colored-in, with just an outline, or with a spray-canned outline).[10] Parts of a drawing can be copied, pasted, and moved to other areas,[11] rotated vertically and horizontally,[12] or erased via pens of six various sizes.[13] An entire painting can also be erased via nine unique visual effects.[13] Animation Land involves the use of the drawing board's tools for creating four, six, and/or nine-frame animations. Elements of one frame can be copied to others for smooth animations to be created.[14] If a character is being animated, the animation box can be set on a background and move throughout it in a "path" recorded by using the mouse in the "path lever" feature.[15]

In the animation and drawing features, stamps can be added to each painting and frame, with 120 existing stamps included in the software.[3] There is a stamp editor that allows the user to create new stamps or edit existing ones via a large tile grid,[16] with the same 15 colors from the drawing board usable in the stamp editor.[17] Up to 15 user-made stamps can be saved to a "personal stamp database".[18] There are also text stamps, such as English, Hiragana, Katakana, and Kanji characters, that can be added and changed in size and color.[19]

The music composer allows users to write pieces either in common time or triple time.[20] There are 15 instruments samples to use that are notated with different icons, including eight melodic sounds (a piano represented by Mario's head, a bell sound represented by a Power Star, a trumpet represented by a Fire Flower, a pulse wave represented by the Game Boy, a horn section sample represented by a goose, a guitar sound represented by an airliner, and an organ represented by a car), three percussion sounds (a bass drum represented by a Super Mushroom, a woodblock represented by a ship, and a bass pluck represented by a heart), and five sound effects (Yoshi's zip, a dog bark, a cat meow, a pig oink, and a baby hiccup).[21] The icons are added to a treble clef. Notes that can be added are limited to a range from the B below middle C to high G.[20] Since no flats or sharps can be added, pieces are restricted to notes of the C major/A minor scale.[22] Other limitations include composing only in quarter notes,[23] a maximum number of three notes on a beat,[20] and a maximum number of measures a song can last (24 bars for 4

4 songs, and 32 bars for 3

4 songs).[22] Pieces made in the composition tool can be played in the animation and coloring book modes.[24]

Reception

[edit]Contemporaneous

[edit]| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Computer and Video Games | 91%[25] |

| Electronic Gaming Monthly | 8.25/10[b] |

| Game Informer | 8.75/10[27] |

| GamePro | 4.75/5[c] |

| Total! | 48%[29] |

| Control | 55%[30] |

| Nintendo Magazine System (Australia) | 70%[31] |

| SNES Force | 82%[32] |

| Super Play | 55%[33] |

| Super Pro | 90%[34] |

| Publication | Award |

|---|---|

| Nintendo Power | Most Innovative[35] |

The Mario Paint and Mouse package sold more than 1 million units by March 1993.[36] Mario Paint is one of the best-selling SNES games at over 2.3 million copies sold worldwide.[37]

Mario Paint's possible age appeal and amount of features were discussed in reviews. While Nintendo Power and GamePro suggested that it had enough features and interactive elements to fascinate a person of any age with "even a remote interest" in artistic ventures,[28][38] other reviews, even from critics who enjoyed the program, suggested the program's limitations made its novelty wear thin to those past its young target demographic[33][30][39] and made its high price tag unjustifiable.[29][30] Total!'s Steve Misery argued that the limitations were inexcusable for a title on a console that can have 250 colors on a screen at a time, stereo audio, and instantly changing graphics.[29] Additionally, he noted the program "goes completely overboard in one area, and then misses others out completely", such as the lack of a zoom feature despite there being multiple flashy ways to erase a painting.[29]

Criticisms of the program brought up in reviews include long save times, "impossible" fine detailing, and the fact that only one collage can be saved at a time.[31]

Mario Paint was honored by the Parents' Choice Award, a non-profit organization recognizing children's educational entertainment.[40] The game also received a platinum award at the 1994 Oppenheim Toy Portfolio Awards.[41] Nintendo Power rated Mario Paint the fourth best SNES game of 1992.[42]

Retrospective

[edit]| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| GameRankings | 72% (4 reviews)[43] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| AllGame | |

| Jeuxvideo.com | 14/20[45] |

| 1UP | 80%[46] |

| Defunct Games | C[47] |

| GameCola | 7.8/10[48] |

| Honest Gamers |

Calling Mario Paint "perhaps the most ingenious and inspired idea Nintendo ever came up with for a product", AllGame rated it 5 out of 5 stars.[44] Honest Gamers stated, "It has very little flaws, if any, is very addictive, and even a child can use it. The games never get old and none of it ever gets tedious. It is one of the best games for the SNES."[49] US Gamer called Mario Paint "an era-appropriate solution to graphics programs on expensive PCs" which is "at least somewhat responsible for our modern era of 2D indie throwback games". It said, "Every single element ... is engineered to make the act of creation fun in and of itself, even if you're just aimlessly doodling."[50] Josh Despain of Defunct Games, however, opined that while it was a "bold and unconventional move" for Nintendo to release a Mario product that was not a game, thus being a "unique piece of video game history", it was nothing more than another simple paint program with a Mario theme.[47]

In 2006, it was rated the 162nd best game made on a Nintendo system in Nintendo Power's Top 200 Games list.[51] In 2014, IGN ranked it as the 105th best Nintendo game in its list of "The Top 125 Nintendo Games of All Time". IGN editor Peer Schneider cited the game's "smart and playful interface" as a "game changer" and commented that "It effectively erased the barriers between creating and playing, making it one of the most memorable and unique games to ever be released on a console."[52]: 2 In 2018, Complex listed Mario Paint 35th on their "The Best Super Nintendo Games of All Time."[53] In 2022, IGN rated Mario Paint 22nd on its "Top 100 SNES Games of All Time", noting that the game inspired different variations of popular songs.[54]

Legacy

[edit]In video games

[edit]Several video game developers have cited Mario Paint as an inspiration. Hirokazu Tanaka, a member of Mario Paint's sound staff, later worked on EarthBound (1994), where some of Mario Paint's sound effects and instrument patches appear. Hirofumi Matsuoka, who directed the development of Mario Paint, later worked on several Mario Artist entries and many of the Wario titles, including WarioWare, Inc.: Mega Microgames! (2003) for the Game Boy Advance, the microgames from which originated from minigames present in Mario Artist: Polygon Studio, which themselves were conceptualized by Kouichi Kawamoto.[55][56] Masahito Hatakeyama, one of the designers of WarioWare D.I.Y. (2009) for the Nintendo DS, cited Mario Paint's drawing board and music composer as the inspiration for D.I.Y.'s drawing and music creation tools, and several development team members cited it as an early inspiration for their video game development careers.[57]

Further references to Mario Paint appear elsewhere in the WarioWare series. WarioWare, Inc.: Mega Microgames! includes Gnat Attack as a microgame. WarioWare: Touched! (2004) for the Nintendo DS includes both a microgame set in Mario Paint's drawing board and a feature called "Wario Paint", which has players color in outlines of WarioWare series characters in a manner similar to Mario Paint's coloring book. WarioWare D.I.Y. includes several easter eggs and callbacks to Mario Paint, including microgames based on the drawing board and Gnat Attack.[57] WarioWare Gold (2018) for the Nintendo 3DS also includes Gnat Attack as a returning microgame. Sound effects from Mario Paint also appear throughout the series.

The Wii Photo Channel features editing functionality similar to Mario Paint, and includes several of the special erasers.[citation needed]

Super Mario Maker (2015), a level creation suite, was originally envisioned as a Mario Paint title for the Wii U.[58] Takashi Tezuka, the game's producer, stated that he "was inspired to bring the fun of Mario Paint into this course editor to make something fun and creative for people to enjoy".[59] US Gamer called Mario Paint an essential part of "the road to Super Mario Maker".[50] As a callback to Mario Paint, Super Mario Maker includes interactive title screen easter eggs, the return of the Gnat Attack minigame, and the appearance of elements and characters originally from Mario Paint, including Undodog, a tan dog functioning as the undo button in both games. Its sequel, Super Mario Maker 2 (2019) for the Nintendo Switch, also features references to Mario Paint, including the return of Undodog as a prominent non-player character in the game's story mode.

Super Mario Odyssey (2017) for the Nintendo Switch includes three costumes for Mario—a black tuxedo, an artists' paint-covered apron, and a classical conductor outfit—that are directly based on artworks created for Mario Paint's promotional materials, with the apron's paired beret also referencing Mario Artist.

A remixed Mario Paint soundtrack medley can be played as background music in the Miiverse stage in Super Smash Bros. for Wii U (2014). Mario Paint is also represented in Super Smash Bros. Ultimate (2018) for the Nintendo Switch through an Assist Trophy called "Flies & Hand", where the flyswatter from Gnat Attack attempts to hit both insects and opposing players.

In animation

[edit]The first episode of Homestar Runner in 1996 was animated using Mario Paint.[60] A primitive introduction video made with Mario Paint can be found in the museum section of the site. A later short in the series, "Strong Bad is a Bad Guy", was made using Mario Paint.

In music

[edit]Since the early 2010s, there has been an online culture of users on forums, Discord, and YouTube creating original songs and covers with Mario Paint's music composer and programs replicating it, including Mario Paint Composer, Advanced Mario Sequencer, and Super Mario Paint.[61][62] Mario Paint covers that have garnered coverage from the press include jeonghoon95's rendition of Daft Punk's "Get Lucky",[63][64][65] a cover of Nicholas Britell's theme for the HBO series Succession,[62][66][67][68] and axelrod777's cover of the Bob-omb Battlefield level music from 1996's Super Mario 64.[69]

Successors

[edit]A downloadable version was released in Japan via the Satellaview broadcast service in 1997. Titled BS Mario Paint: Yuu Shou Naizou Ban (マリオペイントBS版), this version was modified to use a standard controller without the need of a mouse.

A sequel to Mario Paint was titled Mario Paint 64 in development,[70] and then released in 1999 as the Japan-exclusive launch game Mario Artist for the 64DD. Nintendo had commissioned the joint developer Software Creations, who described the game's original 1995 design idea as "a sequel to Mario Paint in 3D for the N64".[70][71] Paint Studio has been described by IGN and Nintendo World Report as being Mario Paint's "direct follow-up"[72] and "spiritual successor"[73] respectively. Likewise bundled with its system's mouse, Paint Studio includes many features from Mario Paint, including new additions such as a gallery and 3D explorable spaces that can be drawn on.[72] Gnat Attack was also intended to appear in Paint Studio, but it was cut before the final release,[74] though it was shown on several magazine previews and some reviewers received copies including it.[72]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "クリエイターズファイル 第102回". Gpara.com. February 17, 2003. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ "Engaged Game Software". Intelligent Systems Co., Ltd. Archived from the original on April 10, 2014. Retrieved August 20, 2009.

- ^ a b c Instruction manual 1992, p. 4.

- ^ a b Instruction manual 1992, p. 30.

- ^ Nintendo Magazine System 1993, p. 39.

- ^ Instruction manual 1992, p. 27.

- ^ Instruction manual 1992, p. 28.

- ^ Instruction manual 1992, p. 7.

- ^ Instruction manual 1992, p. 9.

- ^ Instruction manual 1992, p. 10.

- ^ Instruction manual 1992, p. 14.

- ^ Instruction manual 1992, p. 15.

- ^ a b Instruction manual 1992, p. 8.

- ^ Instruction manual 1992, p. 22–24.

- ^ Instruction manual 1992, p. 24.

- ^ Instruction manual 1992, p. 39.

- ^ Instruction manual 1992, p. 12.

- ^ Instruction manual 1992, p. 13.

- ^ Instruction manual 1992, p. 17–18.

- ^ a b c Instruction manual 1992, p. 20.

- ^ Player's Guide 1993, p. 69.

- ^ a b Player's Guide 1993, p. 71.

- ^ Player's Guide 1993, p. 70.

- ^ Instruction manual 1992, p. 25, 27.

- ^ "CVG Review: Mario Paint" (PDF). Computer and Video Games. No. 133 (December 1992). November 15, 1992. pp. 82–3. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 27, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ Harris, Steve; Semrad, Ed; Alessi, Martin; Sushi-X (October 1992). "Mario Paint". Electronic Gaming Monthly. Vol. 5, no. 39. p. 24.

- ^ "Legacy Review Archives". Game Informer. Archived from the original on December 14, 2018. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ a b N. Somniac (January 1993). "Mario Paint". GamePro. No. 42. p. 90.

- ^ a b c d 'Misery, Steve (October 1992). "Mario Paint". Total!. No. 10. pp. 94–95.

- ^ a b c "Mario Paint". Control. No. 9. May 1993. p. 77.

- ^ a b Nintendo Magazine System 1993, p. 41.

- ^ "The Guide Directory". SNES Force. No. 1. July 1993. p. 94.

- ^ a b Bridgeman, Jez (April 1993). "Mario Paint". Super Play. No. 6. pp. 70–71.

- ^ "Mario Paint". Super Pro. No. 2. January 1993. pp. 92–94.

- ^ "Nintendo Power Awards '92: The NESTERS". Nintendo Power. No. 48. May 1993. pp. 36–9.

- ^ "Nintendo earnings up 2 percent". United Press International (UPI). Redmond, Washington. May 21, 1993. Archived from the original on December 24, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ^ CESA Games White Papers. Computer Entertainment Supplier's Association.

- ^ Sinfield, George; Noel, Rob (August 1992). "Mario Paint". Nintendo Power. Vol. 39. pp. 104–105.

- ^ Instruction manual 1992, p. 41.

- ^ "Kid's; Books, Toys, Videos Honored". Associated Press. January 14, 1993. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Oppenheim, Joanne and Stephanie (1993). "Computer Software/CD-ROM - Life After Arcade: Getting Value From Sega and Nintendo - 'Mario Paint'". The Best Toys, Books & Videos for Kids. Oppenheim Toy Portfolio Guide Book. Vol. 1 (1st ed.). New York: Harper Perennial. p. 279. ISBN 0-06-273196-3.

- ^ "Top 10 of 1992". Nintendo Power. Vol. 44. January 1993. p. 118. Retrieved January 23, 2022.

- ^ "Mario Paint Gamerankings review score". Archived from the original on May 4, 2019.

- ^ a b House, Michael Ll. "Mario Paint - Review". Allgame. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ de Anagund, L'avis (July 30, 2009). "Test: Mario Paint". Jeuxvideo.com (in French). Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ "Mario Paint (SNES)". 1UP. March 16, 2002. Archived from the original on August 16, 2024. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ a b Despain, Josh (January 6, 2014). "Mario Paint". Defunct Games. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ Johnson, Allec (May 2004). "Mario Paint". GameCola. Archived from the original on October 16, 2004. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ a b Aganar. "Mario Paint (SNES) review". Honest Gamers. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ a b Mackey, Bob (September 11, 2015). "The Road to Super Mario Maker". US Gamer. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved November 28, 2015.

- ^ "NP Top 200". Nintendo Power. Vol. 200. February 2006. pp. 58–66..

- ^ "The Top 125 Nintendo Games of All Time". IGN. September 24, 2014. Archived from the original on March 24, 2015. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ Knight, Rich (April 30, 2018). "The Best Super Nintendo Games of All Time". Complex. Archived from the original on January 9, 2022. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ Top 100 SNES Games of All Time - IGN.com, archived from the original on January 23, 2012, retrieved September 8, 2022

- ^ Sakamoto, Yoshio; Nakada, Ryuichi; Takeuchi, Ko; Abe, Goro; Sugioka, Taku; Mori, Naoko (April 7, 2006). "Nintendo R&D1 Interview" (Interview). Video Games Daily. Archived from the original on February 20, 2010. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- ^ Mirachian, Darron (September 29, 2021). "Three decades of Wario all started with a name". Polygon. Archived from the original on April 20, 2023. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ a b "Iwata Asks". Nintendo of Europe. Archived from the original on August 16, 2024. Retrieved January 9, 2015.

- ^ "What Super Mario Bros.' Creators Think of Super Mario Maker". Time. September 11, 2015. Archived from the original on April 20, 2023. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ Lien, Tracey (June 13, 2014). "Mario Maker started out as a tool for Nintendo's developers". Polygon. Archived from the original on October 17, 2014. Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ^ "Super NES" (SWF). homestarrunner.com. 1996. Archived from the original on September 10, 2012. Retrieved January 3, 2007.

- ^ Henges, Elizabeth (February 6, 2020). "Meet the musicians who compose in Mario Paint". The Verge. Archived from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ a b Grimm, Peter (October 5, 2019). "Succession TV Show Theme Remade In Mario Paint". Game Rant. Archived from the original on October 31, 2021. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Greenwald, David (September 3, 2013). "'Get Lucky' Goes 16-Bit With 'Mario Paint' Cover: Watch". Billboard. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Reißmann, Ole (September 10, 2013). "Angeklickt: Daft Punk Get Lucky Mario Paint Composer". Der Spiegel. Archived from the original on August 16, 2024. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Maloney, Devon (September 9, 2013). "Man's First Try at Mario Paint Composition Results in Perfect Cover of 'Get Lucky'". Wired. Archived from the original on August 16, 2024. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Bryan, Chloe (October 4, 2019). "The 'Succession' theme song recreated in 'Mario Paint' is simply delightful". Mashable. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Chitwood, Adam (October 3, 2019). "The Succession Theme Song in Mario Paint Is Pure Joy". Collider. Archived from the original on March 29, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Bitran, Tara (November 20, 2019). "'Succession' and the Theme Song That Launched 100 Memes". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Kyle (May 16, 2018). "Fan Recreates Super Mario 64 Music in Mario Paint". Game Freaks 365. Archived from the original on March 6, 2021. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ a b Miyamoto, Shigeru (July 29, 1997). "Miyamoto Reveals Secrets: Fire Emblem, Mario Paint 64" (Interview). Interviewed by IGN staff. Archived from the original on April 17, 2001. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ^ "Mario Artist: Paint Studio / Sound Studio". Zee-3 Digital Publishing. Archived from the original on December 10, 2022. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ^ a b c Schneider, Peer (August 22, 2000). "Mario Artist: Paint Studio (Import)". IGN. Archived from the original on September 16, 2022. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ^ Bivens, Danny (October 29, 2011). "Nintendo's Expansion Ports: Nintendo 64 Disk Drive". Nintendo World Report. Archived from the original on October 27, 2014. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ^ "Proto:Mario Artist Paint Studio". The Cutting Room Floor. Archived from the original on April 20, 2023. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Mario Paint instruction manual. Nintendo of America. 1992. pp. 1–34.

- "Mario Paint Nintendo Player's Guide". Nintendo Power. 1993. pp. 1–120.

- "Mario Paint". Nintendo Magazine System. No. 4. July 1993. pp. 38–41.

External links

[edit]- Official website (in Japanese)

- Mario Paint at MobyGames

- 1992 video games

- Drawing video games

- Intelligent Systems games

- Nintendo Research & Development 1 games

- Raster graphics editors

- Super Nintendo Entertainment System-only games

- Super Nintendo Entertainment System games

- Video games about insects

- Video games developed in Japan

- Video games scored by Hirokazu Tanaka

- Video games scored by Kazumi Totaka

- Single-player video games

- Mario spin-off games